Lectures. Concept and classification of transaction costs Give the main options for classifying transaction costs

Volchik V.V. Lectures on institutional economics

Transaction costs

1. The economic nature of transaction costs.

2. Classifications of transaction costs.

3. Transaction costs and institutions.

Literature

Main:

1. Shastitko A.E. New institutional economics. M., 2002. Ch. 6.7.

2. North D. Institutions, institutional changes and the functioning of the economy. M., 1997.

3. Volchik V.V. Course of lectures on institutional economics. Rostov-on-Don: RSU Publishing House, 2000. Lecture 3.

4. Malakhov S. In defense of liberalism (to the question of the balance of transaction costs and costs of collective action) // Questions of Economics. 1998. No. 8.

5. Kapelyushnikov R.I. Economic theory of property rights. M., 1990.

6. Eggertsson T. Economic behavior and institutions. M.: Delo, 2001.

Additional:

1. Menard K. Economics of Organizations. - M.: INFRA-M, 1996.

2. Williamson O. Economic institutions of capitalism. St. Petersburg, 1996.

3. Volchik V.V. Efficiency of the market process and the evolution of institutions // News of universities of the North Caucasus region. Public Sciences . 2002. No. 4.

4. Demsetz H. The Firm in Economic Theory: A Quiet Revolution. American Economic Review, 1997, vol. 87, No. 2, pp. 426-429.

5. Belokrylova O.S., Volchik V.V., Muradov A.A. Institutional features of income distribution in a transition economy. Rostov-on-Don: Publishing house Rost. un-ta. 2000.

1. Economic nature of transaction costs

In economics, back in the 19th century, some economists suggested that in a real economy, concluding transactions between agents is associated with certain costs. One of these scientists was the founder of the Austrian school, Carl Menger.

To understand the essence of Menger's argument, it is necessary to understand his concept of the productivity of economic exchange. Economic exchange occurs only when each participant, carrying out an act of exchange, receives some increase in value to the value of the existing set of goods. This is proven by Carl Menger in his work “Foundations of Political Economy”, based on the assumption of the existence of two participants in the exchange. The first has good A, which has value , and the second-

good B with value

![]() . As a result of the exchange that took place between them, the value of goods at the disposal of the first will be , and the second – . From this we can conclude that in the process of exchange, the value of the good at the disposal of each participant increased by a certain amount. This example shows that activities related to exchange are not a waste of time and resources, but are as productive as the production of material goods.

. As a result of the exchange that took place between them, the value of goods at the disposal of the first will be , and the second – . From this we can conclude that in the process of exchange, the value of the good at the disposal of each participant increased by a certain amount. This example shows that activities related to exchange are not a waste of time and resources, but are as productive as the production of material goods.

When exploring exchange, one cannot help but dwell on its limits. The exchange will take place until the value of the goods at the disposal of each participant in the exchange will, according to his estimates, be less than the value of those goods that can be obtained as a result of the exchange. This thesis is true for all exchange counterparties. Using the symbolism of the above example, an exchange occurs if for the first and for the second participant in the exchange, or if and .

Therefore, we can write the equation:

,(1)

Where - assessing value after exchange;

- assessing value before exchange;

- increase in value; in all voluntary exchanges that took place.

Equation (1) describes a single act of exchange. The key here is the indicator characterizing the increase in value or its difference and, consequently, the very possibility and profitability of exchange.

Menger noted that in reality, cases when the “victims of an exchange operation” are reduced to a minimum, and counterparties receive all the benefits, are rare, and it is unlikely that in reality one will encounter such a situation in which the act of exchange occurs completely without economic sacrifices, at least the last limited to just wasting time. Freight, fees, customs duties, accidents, postage, insurance, provisions and commissions, courtage, weight packaging and warehouse fees, maintenance of people engaged in trade and their assistants in general, cash circulation costs, etc. - all this is nothing more than the economic sacrifices required by exchange transactions; they take away part of the economic benefit that can be extracted from the existing exchange relationship, and often even make it impossible to realize it where it would still be conceivable if it were not for these “costs” in the general, national economic sense of the word. From the above definition, we see that Menger actually defined transaction costs, which were later rediscovered by Coase.

It is also possible to introduce transaction costs into a model of economic exchange to illustrate its limits. Let's return to equation (1). If we take the transaction costs of the first individual as , and the second as , then we can write:

(2)

Obviously, the exchange will be possible if is a positive number, or

![]() .

.

The problem of concluding deals and the influence of institutions on this process was reflected in the works of representatives of old institutionalism. Thus, J. Commons assigned one of the central places in his theoretical models to the concept of transaction.

According to Commons, a transaction is not an exchange of goods, but an alienation and appropriation of property rights and freedoms created by society. This definition makes sense (according to Commons) due to the fact that institutions ensure the spread of the will of an individual beyond the area within which he can influence the environment directly through his actions, i.e. beyond the scope of physical control, and, therefore, turn out to be transactions, as opposed to individual behavior as such or the exchange of goods.

Commons distinguished three main types of transactions:

1. The transaction of the transaction serves to carry out the actual alienation and appropriation of property rights and freedoms, and its implementation requires mutual consent of the parties, based on the economic interest of each of them.

In the transaction, the condition of symmetrical relations between counterparties is observed. The distinctive feature of a transaction, according to Commons, is not production, but the transfer of goods from hand to hand.

2. Management transaction – the key here is the management relationship of subordination, which involves such interaction between people when the right to make decisions belongs to only one party. In a management transaction, behavior is clearly asymmetrical, which is a consequence of the asymmetry of the position of the parties and, accordingly, the asymmetry of legal relations.

3. Rationing transaction - in this case, the asymmetry of the legal position of the parties is preserved, but the place of the managing party is taken by a collective body that performs the function of specifying rights. Rationing transactions include: the preparation of a company budget by the board of directors, the federal budget by the government and approval by a representative body, the decision of an arbitration court regarding a dispute arising between operating entities through which wealth is distributed. There is no control in the rationing transaction. Through such a transaction, wealth is allocated to one or another economic agent.

The presence of transaction costs makes certain types of transactions more or less economical depending on the circumstances of time and place. Therefore, the same operations can be mediated by different types of transactions depending on the rules that they order.

The concept of transaction costs was introduced by R. Coase in the 1930s in his article “The Nature of the Firm.” It has been used to explain the existence of hierarchical structures that are antithetical to the market, such as firms. R. Coase associated the formation of these “islands of consciousness” with their relative advantages in terms of saving on transaction costs. He saw the specifics of the company's functioning in the suppression of the price mechanism and its replacement with a system of internal administrative control.

According to Coase, transaction costs are interpreted as “the costs of collecting and processing information, the costs of negotiations and decision-making, the costs of monitoring and legal protection of the execution of a contract.”

Within the framework of modern economic theory, transaction costs have received many interpretations, sometimes diametrically opposed.

Thus, K. Arrow defines transaction costs as the costs of operating an economic system.

Many economists use an analogy with friction when explaining the phenomenon of transaction costs. Coase has a reference to Stigler's words: Stigler said of the “Coase theorem”: “A world with zero transaction costs turns out to be as strange as a physical world without friction forces. Monopolists could be compensated to behave competitively, and insurance companies would simply not exist.”

Based on such assumptions, conclusions are drawn that the closer an economy is to the Walrasian general equilibrium model, the lower its level of transaction costs, and vice versa.

In D. North’s interpretation, transaction costs “consist of the costs of assessing the useful properties of the object of exchange and the costs of ensuring rights and enforcing their compliance.” These costs inform social, political, and economic institutions.

G. Demsets understands this category of costs “as the costs of any activity associated with the use of the price mechanism. Similarly, he defines management costs as “costs associated with conscious management of the use of resources” and proposes to use the following abbreviations: PSC (price system costs) and MSC (management system costs) - respectively, the costs of using the price mechanism and the management mechanism.

Also in the New Institutional Economic Theory (NIET), the following view of the nature of transaction costs is widespread: “The fundamental idea of transaction costs is that they consist of the costs of drawing up and concluding a contractex ante, as well as the costs of contract supervision and enforcementex postas opposed to production costs, which are the costs of actually fulfilling the contract. To a large extent, transaction costs are relations between people, and production costs are costs of relations between people and objects, but this is a consequence of their nature rather than their definition.

In the theories of some economists, transaction costs exist not only in a market economy (Coase, Arrow, North), but also in alternative methods of economic organization and, in particular, in a planned economy (S. Chang, A. Alchian). Thus, according to Chang, maximum transaction costs are observed in a planned economy, which ultimately determines its inefficiency.

2. Classifications of transaction costs

A significant number of types of classifications of transaction costs is a consequence of the multiplicity of approaches to the study of this problem. O. Williamson distinguishes two types of transaction costs: ex ante And ex post. To costs like ex ante include the costs of drawing up a draft agreement and negotiating it. Type costs ex post include organizational and operational costs associated with the use of the management structure; costs arising from poor adaptation; litigation costs arising in the course of adapting contractual relationships to unforeseen circumstances; costs associated with fulfilling contractual obligations.

K. Menard divides transaction costs into 4 groups:

Isolation costs;

Costs of scale;

Information costs;

Costs of behavior.

In the functioning of any organization, there is, first of all, the problem of inseparability, and the total costs of separation arise precisely for this reason. In most cases, economic activity is driven by cooperative efforts, and it is impossible to accurately measure the marginal productivity of each factor involved and its reward. K. Menard gives the example of a team of loaders: “To set the wages of the team, using the organization turns out to be more effective than using the market. The organization surpasses the market even when the latter requires too detailed, otherwise impossible differentiation.”

Further, K. Menard highlights the costs of scale. The larger the scale of the market, the more impersonal the acts of exchange are, and the more necessary it is to develop institutional mechanisms that determine the nature of the contract, the rules for its application, sanctions for non-compliance with obligations, etc. The establishment of employment contracts designed to stabilize the relationship between employer and employee, supply contracts to ensure the regularity of the flow of costs, is partly explained by the need to establish “trust, which the scale of markets and periodic contracting would make both problematic and expensive.”

Information costs represent a separate category. The transaction is associated with an information system, the role of which in the modern economy is played by the price system. This category includes costs that cover all aspects of the functioning of an information system: coding costs, signal transmission costs, training costs to use the system, etc. Every system, through its functioning, creates various interferences, which reduce the accuracy of price signals. The latter cannot be too differentiated, since the manipulation of a very large number of signals is associated with prohibitive costs. The organization in this case allows you to reduce costs by using less of the market and limiting the number of signals sent and received."

The last group consists of behavioral costs. They are associated with “selfish behavior of agents”; a similar concept accepted and used now is “opportunistic behavior.”

The most famous domestic typology of transaction costs is the classification proposed by R. Kapelyushnikov:

1. Costs of searching for information. Before a transaction is made or a contract is concluded, you need to have information about where you can find potential buyers and sellers of the relevant goods and factors of production, and what the current prices are. Costs of this kind consist of the time and resources required to conduct the search, as well as losses associated with the incompleteness and imperfection of the acquired information.

2. Negotiation costs. The market requires the diversion of significant funds for negotiations on the terms of exchange, for the conclusion and execution of contracts. The main tool for saving this kind of costs is standard (standard) contracts.

3. Measurement costs. Any product or service is a set of characteristics. In the act of exchange, only some of them are inevitably taken into account, and the accuracy of their assessment (measurement) can be extremely approximate. Sometimes the qualities of a product of interest are generally immeasurable, and to evaluate them one has to use surrogates (for example, judging the taste of apples by their color). This includes the costs of appropriate measuring equipment, the actual measurement, the implementation of measures aimed at protecting the parties from measurement errors and, finally, losses from these errors. Measurement costs increase with increasing accuracy requirements.

Enormous savings in measurement costs have been achieved by mankind as a result of the invention of standards for weights and measures. In addition, the goal of saving these costs is determined by such forms of business practices as warranty repairs, branded labels, purchasing batches of goods based on samples, etc.

4. Costs of specification and protection of property rights. This category includes the costs of maintaining courts, arbitration, government bodies, the time and resources required to restore violated rights, as well as losses from their poor specification and unreliable protection. Some authors (D. North) add here the costs of maintaining a consensus ideology in society, since educating members of society in the spirit of observing generally accepted unwritten rules and ethical standards is a much more economical way to protect property rights than formalized legal control.

5. Costs of opportunistic behavior. This is the most hidden and, from the point of view of economic theory, the most interesting element of transaction costs.

There are two main forms of opportunistic behavior. The first one wears Name moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs when one party in a contract relies on another party, and obtaining actual information about his behavior is costly or impossible. The most common type of opportunistic behavior of this kind is shirking, when an agent works with less efficiency than is required of him under the contract.

Particularly favorable conditions for shirking are created in conditions of joint work by a whole group. For example, how to highlight the personal contribution of each employee to the overall result of activities<команды>factory or government agency? We have to use surrogate measurements and, say, judge the productivity of many workers not by results, but by costs (such as labor time), but these indicators often turn out to be inaccurate.

If the personal contribution of each agent to the overall result is measured with large errors, then his reward will be weakly related to the actual efficiency of his work. Hence the negative incentives that encourage shirking.

In private firms and government agencies, special complex and expensive structures are created whose tasks include monitoring the behavior of agents, detecting cases of opportunism, imposing penalties, etc. Reducing the costs of opportunistic behavior is the main function of a significant part of the management apparatus of various organizations.

Second form opportunistic behavior – extortion. Opportunities for it appear when several production factors work in close cooperation for a long time and become so accustomed to each other that each becomes indispensable and unique to the other members of the group. This means that if some factor decides to leave the group, then the remaining participants in the cooperation will not be able to find an equivalent replacement for it on the market and will suffer irreparable losses. Therefore, the owners of unique (in relation to a given group of participants) resources have the opportunity for blackmail in the form of a threat to leave the group. Even when “extortion” remains only a possibility, it always turns out to be associated with real losses. (The most radical form of protection against extortion is the transformation of interdependent (interspecific) resources into jointly owned property, the integration of property in the form of a single bundle of powers for all team members).

In a market economy, a company’s costs can be divided into three groups: 1) transformational, 2) organizational, 3) transactional.

Transformation costs – costs of transforming the physical properties of products in the process of using production factors.

Organizational costs – costs of ensuring control and distribution of resources within the organization, as well as costs of minimizing opportunistic behavior within the organization.

Transaction and organizational costs are interrelated concepts; an increase in some leads to a decrease in others and vice versa.

3. Transaction costs and institutions

The role of institutions in a market economy is to reduce transaction costs. Minimizing transaction costs leads to an increase in the degree of competitiveness of the market structure and, consequently, in most cases to an increase in the efficiency of the functioning of the market mechanism. The presence of institutional barriers to competition between business entities leads to the opposite result. Therefore, their study assumes a clear substantive description of the category “competition”.

As D. North and J. Wallis have shown, the development of market relations in a transition economy determines the emergence and development of the transaction sector. According to their interpretation, the transaction sector includes industries whose main function is to ensure the redistribution of resources and products with the lowest average transaction costs.

In developed countries, there is a tendency to reduce specific transaction costs, which determines an increase in the number of transactions, and therefore the volume of total costs in the economy may increase. However, in Russia, due to the existence of ineffective institutions, administrative barriers and restrictions, average transaction costs remain at an unacceptably high level, which limits the volume and number of transactions, leading to an increase in the marginal costs of enterprises exposed to them.

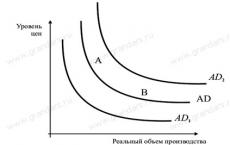

Thus, the impact of growing transaction costs on market equilibrium is carried out through the mechanism of introducing additional taxes.As can be seen from Figure 1, in the market for an individual product this leads to an increase in price and a decrease in sales volumes. This position of the model is consistent with the realities of economic practice in Russia, where relatively high prices are observed in comparison with the income of the population.

Figure 1. Equilibrium shift due to rising transaction costs

The higher the level of transaction costs TC, the greater the shift in the supply curve.

The use of transaction costs as a tool of economic analysis provides opportunities for interpreting institutional equilibrium and its modification in a transition economy.

Demand for institutions comes from individuals, groups, or society as a whole, since the social or group costs of creating and maintaining an institution should be less than the costs that arise in its absence. The value of transaction costs becomes not only a quantitative indicator of the degree of market imperfection, but also a quantitative expression of the costs of the absence of an institution. Therefore, the higher the transaction costs, the higher the demand for institutional regulation, which complements and even replaces market regulation.

According to modern institutional theory, the effectiveness of the functioning of a particular institution is determined by the amount of savings on transaction costs. Therefore, the costs of engineering by society institutions in the labor market will be correlated with the value transaction costs ( A TC), which allows you to express through them demand function for institutions, and the costs of collective action ( C.A.C. ), which characterize supply of institutions “on the institutional market”. The process of establishing institutional equilibrium is presented in Figure 2 ( N – the number of individuals included in the sphere of action of institutions, AIC – institutional costs – transaction costs, the reduction of which is ensured by institutions, and the costs of creating institutions).

Rice. 2. Institutional balance

In the presented traditional model of institutional equilibrium, the fundamental nature may be different degrees of bargaining power of the parties, if we consider the whole society from the demand side for institutions, and from the supply side - the state as a monopolist, producing formal institutions and not only enforcing the implementation of the rules and norms it establishes, but also, due to this, as well as certain control over information flows, forming public opinion.

It is beneficial for the state to carry out a kind of price discrimination in the institutional market, i.e. limit access to certain rights and institutionalized forms of economic activity based on group affiliation. In turn, this determines both the methods of generating income and their amount, depending on the “price” paid in the form of overcoming barriers expressed in high transaction costs of using institutions.

Thus, adjusting the model of a competitive market of institutions in a transition economy consists of taking into account the monopoly power of the state offering formal institutions on the institutional market, which has a significant impact on the asymmetry of income distribution.

Rice. 3. Modification of institutional equilibrium

In this case, the demand and supply curves of institutions change their shape and slope. The supply curve (or the collective action cost curve, i.e. the social costs of creating institutions, collective action cost - CAC) becomes horizontal, since the creation of an institution is associated with fixed costs for maintaining the state apparatus. The demand curve (or aggregate transaction cost curve - ATC) takes on a positive slope due to the distributive nature of the institutions being created. Therefore, with an increase in the number of individuals included in its sphere of action (N), their comparative benefits decrease due to an increase in transaction costs that block entry into the distribution of certain benefits.

Thus, the existence of a monopoly on institutions is manifested in the differentiation of access to opportunities for economic activity depending on the criteria that are significant under a particular government structure. This, in turn, determines the distribution of income, creating advantages for certain groups to receive them, but at the same time blocking them for the rest of the population. 1986.

Belokrylova O.S., Volchik V.V., Muradov A.A. Institutional features of income distribution in a transition economy. Rostov-on-Don: Publishing house Rost. un-ta. 2000. pp. 90-93.

Topic 2.Transaction costs

1. The essence of transaction costs.

2. Transaction costs in economic theory. Coase theorem.

3. Classifications of transaction costs.

4. Ways to minimize transaction costs.

question. The essence of transaction costs

The introduction of the concept of “transaction costs” into economic analysis was a major theoretical achievement. Recognition of the “non-free” nature of the very process of human interaction made it possible to shed new light on the nature of economic reality: “Without the concept of transaction costs, which is largely absent in modern economic theory, it is impossible to understand how the economic system works, to productively analyze a number of problems arising in it, and provide a basis for making policy recommendations. (Coase, R. Firm, market and law / R. Coase. M., 1993. P. 6)

K. Menger wrote about the possibility of the existence of exchange costs and their influence on the decisions of exchanging subjects in his “Foundations of Political Economy.” Economic exchange occurs only when each participant, carrying out an act of exchange, receives some increase in value to the value of the existing set of goods, based on the assumption of the existence of two participants in the exchange. The first has good A, which has a value W, and the second has good B with the same value W. As a result of the exchange that has taken place, the value of goods at the disposal of the first will be W + x, and the second - W + y. From this we can conclude that during the exchange process, the value of the good for each participant increased by a certain amount. The example shows that activities related to exchange are not a waste of time and resources, but are as productive as the production of material goods.

When exploring exchange, one cannot help but dwell on the analysis of its limits. The exchange occurs until the value of the goods at the disposal of each participant in the exchange is, according to his estimates, less than the value of those goods that can be obtained as a result of the exchange. This thesis is true for all exchange counterparties.

Using the symbolism of the above example, we find that the exchange occurs if W(A)< W + х для первого и W(В) < W + у для второго участника обмена, или если х >0 and y > 0.

So far we have considered exchange as a process that occurs without costs. But in a real economy, any act of exchange is associated with certain costs. Criticism of the position of the neoclassical theory “exchange occurs without costs” served as the basis for introducing a new concept into economic analysis - transaction costs TgC (transaction cost) in contrast to production costs PC (production cost)

Manufacturing costs are the costs that accompany the process of physically changing a material, resulting in a product that has a certain value. These costs include not only the costs of processing the material, but also the costs associated with planning and coordinating the production process, if the latter concerns technology and not relationships between people (in the literature they are often referred to as transformation costs).

Exchange costs are called transaction costs. They are usually interpreted as “the costs of collecting and processing information, the costs of negotiations and decision-making, the costs of monitoring and legal protection of the execution of the contract.” Unlike production costs, transaction costs are not associated with the value creation process itself; they provide a transaction, that is, they create goods whose properties are valuable for an individual or a collective agent of the economy (firm, association).

The concept of “transaction” was first introduced into scientific circulation by J. Commons. A transaction is not an exchange of goods, but an alienation and appropriation of property rights and freedoms created by society.

This definition makes sense due to the fact that institutions ensure the extension of the will of an individual beyond the area within which he can influence the environment directly through his actions, i.e., beyond physical control, and, therefore, turn out to be transactions in contrast to individual behavior as such or the exchange of goods. Therefore, the concept of “transaction” means the process of moving/reproducing property rights. Close in meaning is the concept of “deal”. The transaction differs from the latter in its greater coverage of economic phenomena, which can be shown using the classification of transactions proposed by J. Commons:

1. Negotiation transaction. The main feature of this type of transaction is the symmetrical nature of the relations between the parties, i.e., the absence of command and subordination. The transfer of property rights is the result of a voluntary agreement between equal parties. The concept of a deal coincides with the concept of a negotiated transaction, and, thus, a deal, unlike a transaction in general, is a special case of it.

2. Management transaction. The asymmetrical nature of the relations between the parties is assumed, i.e. they are built on the principle of command and subordination, and these relations take place between individuals. A management transaction involves the transfer of property rights as a result of the command of one individual and the subordination of another (the simplest example is the relationship between a boss and a subordinate in a company). There is a transfer of a certain property right, namely the freedom to manage time at one’s own discretion, from a subordinate to a superior. Even if there is an employment contract, during the conclusion of which there was legal symmetry between them, this transaction is governing because its participants do not negotiate regarding each labor transaction.

3. Rationing transaction. In this case, there is also an asymmetrical legal status of the parties, but unlike a management transaction, here the commands are given by a collective body, and subordination comes from individuals. These include the relationship between the state and the population, which is characterized by the transfer of property rights; Let's say, there is an alienation of property rights to a part of the income of some people (income tax) and their appropriation by other people (social benefits). Such a transaction requires command from the collective body and obedience from the individuals.

The foundations of transaction cost theory were outlined by R. Coase in his classic articles “The Nature of the Firm” (1937) and “The Problem of Social Costs” (1960). The identification of such an important component as information costs in transaction costs was carried out by J. Stigler in 1961 in his work “The Economic Theory of Information”. The problem of uneven distribution of information between economic agents (information asymmetry) was first identified by J. Akerlof in his work “The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism” (1970).

The concept of “transaction costs” was introduced into scientific circulation by R. Coase to explain the existence of hierarchical structures such as firms that are opposed to the market. He associated the formation of these “islands of consciousness” with their relative advantages in terms of savings on transaction costs. Coase saw the specificity of the functioning of the company in the suppression of the price mechanism and its replacement with a system of internal administrative control.

Initially, Coase himself considered transaction costs only the costs that arise when using the price market mechanism. His followers began to include in their composition the costs associated with the use of administrative control mechanisms. With this expanded interpretation, the concept of “transactions” applies both to the relationships that develop between organizations and to the relationships that develop within them.

The emergence of the theory of transaction costs as an integral scientific concept is associated, first of all, with the works of such researchers as A. Alchian, G. Demset, O. Williamson, S. Chey, I. Bartzel, M. Jensen and others. Throughout the history of its existence This theoretical direction has repeatedly proposed various definitions of the category of transaction costs and attempts have been made to typify them.

Within the framework of modern economic theory, transaction costs have received many interpretations, sometimes diametrically opposed. For example, K. Arrow defines transaction costs as the costs of operating an economic system. (Arrow, K. Possibilities and limits of the breakthrough as a mechanism for allocating resources / K. Arrow // TNESIS.1993. Vol. 1. Issue 2. P. 53.)

Based on such assumptions, economists conclude: the closer the economy is to the Walrasian general equilibrium model, the lower the level of transaction costs, and vice versa.

We can say that transaction costs act as a kind of measure of the imperfection of the economy: the more reality differs from the ideal picture described by neoclassical theory, the less perfect the market is. The totality of institutions available in society determines how different reality is from the ideal, and the value of transaction costs reflects the content of the institutional system. Based on this, many economists interpret transaction costs as costs associated with the creation, change, consolidation and use of institutions by economic entities.

In the theories of some economists, transaction costs exist not only in a market economy (R. Coase, K. Arrow, D. North), but also in alternative methods of economic organization, and in particular in a planned economy (S. Chang, A. Alchian, G. . Demets).

Thus, transaction costs could be defined as the costs of economic interaction, in whatever forms it may take.

“Transaction costs cover the costs of making decisions, developing plans and organizing future activities, negotiating about its content and conditions when two or more participants enter into a business relationship; costs of changing plans, revising the terms of the transaction and resolving controversial issues when this is dictated by changed circumstances; the costs of ensuring that participants comply with the agreements reached. Transaction costs also include any losses arising from the ineffectiveness of joint decisions, plans, concluded contracts and created structures; ineffective responses to changed conditions; ineffective protection of agreements. In a word, they include everything that, one way or another, is reflected in the comparative performance of various methods of allocating resources and organizing production activities" (North, D. Institutions, institutional changes and the functioning of the economy. Ch. 4. pp. 45-55.)

The definitions of transaction costs are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The most famous definitions of transaction costs

| Author | Definition |

| K. Arrow | Transaction costs are the costs of operating an economic system |

| J. Winneski | These are the costs associated with the creation, change, consolidation and use of institutions by economic entities |

| D. North | These are costs that consist of the costs of assessing the useful properties of the object of exchange and the costs of ensuring rights and enforcing their compliance. |

| D. North | Production costs are costs determined by the state of the productive forces; transaction costs are costs determined by the nature of production relations |

| S. Chung | In the broadest sense, transaction costs consist of those costs that would be unimaginable in Robinson Crusoe's economics. |

| P. Milgrom, J. Roberts | Transaction costs include any losses arising from the ineffectiveness of joint decisions, plans, concluded contracts and created structures; ineffective responses to changed conditions; ineffective protection of agreements. In a word, they include everything that, one way or another, is reflected in the comparative performance of various methods of resource allocation and organization of production activities |

The magnitude of transaction costs is very significant. Let us estimate the value of transaction costs based on known data (Table 2).

Table 2. Estimation of transaction costs

As we can see, the average size of the transaction sector currently ranges from 50 to 70%.

There is significant growth in the transaction sector of the economy. The share of the transaction sector in the economy is estimated as a trend (straight line) from 25% in 1870 to 65% in 2000.

The indicated values of transaction costs are typical for countries with a stationary economy. For countries with economies in transition, these values may be significantly higher.

In addition, the distinction between the transaction sector as a whole and the transaction costs of the firm allows us to evaluate the savings on transaction costs due to the formation of the firm itself as an institution. This value is about 50%. Forming a firm saves on overall costs by transforming transaction costs of independent agents on the open market into organizational costs within the firm .

A significant share of transaction costs in developed countries is caused by an increase in the number of potential subjects of economic relations, and, consequently, the number of transactions carried out by them. At the same time, in countries with transition economies, the high level of transaction costs is also due to the fact that they have not yet developed a mechanism for interaction between government agencies and business entities.

The Russian economy of the transition period clearly demonstrated the connection between the magnitude of transaction costs and the imperfection of the real market (see Table 3).

Table 3. Estimation of the value of transaction costs of the process of institutional transformation in Russia in the mid-1990s.

| Additional transaction costs | Share of transaction costs in the firm’s total costs, % |

| Costs associated with corruption Costs of barter transactions compared to cash flow Costs associated with administrative barriers Costs associated with the shadow part of working time | +10 +30 +3 +12 |

| Total: | +55 |

Today, the share of transaction costs in enterprise costs is about 11%. Such a value indicates the end of mostly transitional processes in society. At the same time, it is still very far from the level of several percent typical of developed countries with stable economies.

Materials, transportation, etc.), and with the indirect costs associated with this production for collecting and searching for all the information necessary for the activity, concluding various transactions, contracts, agreements, etc.

This term was first introduced by the American economist R. Coase in his work “The Nature of the Firm” in 1937, who later won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his study of transaction costs in 1991.

There are several types of transaction costs. Let us list the most important of them.

- Costs of searching for information. This refers, first of all, to the costs associated with finding counterparties for business and other transactions, as well as the search for the most favorable conditions in terms of price, purchase and sale. Before concluding the necessary transaction, the economic agent collects the necessary information about the counterparty (for example, an insurance company, before insuring your life, will require many certificates from you about your health status, and will also check their accuracy). Prices for the same good can differ significantly in different markets, and each of us knows that people with lower incomes, before buying the necessary goods, will first go around several stores and markets in search of a low price.

- Costs of concluding a business agreement (contract). It takes money and time to reach the necessary agreement between the parties. For example, let's say you're about to publish a detective novel you've written. You will need a knowledgeable agent to handle all the necessary negotiations with the publisher, so funds will be required to pay the agent's services. The negotiations themselves will take some time. And finally, signing the long-awaited contract, as well as a friendly dinner with the publisher, will also be transaction costs of concluding a contract.

- Measurement costs. All goods have various properties that bring utility to their owner. For example, you are going to buy a fur coat. Before making a purchase, you need to make sure of the quality of the fur, coloring, tailoring, etc. Before making a choice, a picky buyer will wrinkle the fur, shake the fur coat, try to pull out the lint, and maybe even smell it in order to determine the quality of the workmanship. In this case, measurement costs make it difficult for those who do not have knowledge about the product to purchase. A property such as a trademark (brand) of a well-known company minimizes the cost of measurement, but in this case no one is immune from counterfeiting. Also, measurement costs are associated with the purchase of measuring equipment (calculators, scales, dosimeters, cash registers, etc.).

- Costs of specification and protection of property rights. It can be noted that any specification, as well as the protection of property rights, is associated with the precise definition of an object or subject of property, law enforcement agencies, the functioning of the judicial system, etc. As a striking example, we can consider the activities of many private small businesses in the recent past of Russia. In fact, the private property rights of any company must be protected by the state, as in any civilized country in the world with a developed market economy. But, if for some reason the state does not cope with this task in full, then private business resorts to alternative means of protecting its property. In other words, companies resort to searching for so-called “roofs” that perform security functions for a fee.

- Costs of opportunistic behavior. Those. costs associated with dishonesty and deception, concealment of information that economic agents may encounter in their activities. For example, identifying and punishing a dishonest counterparty who violates the terms of the contract entails considerable costs. Costs are also required to protect oneself from such opportunistic behavior. For example, in currency exchange offices and cash desks of many financial and credit institutions there are special devices for detecting counterfeit banknotes. When purchasing honey, connoisseurs must check it with a special chemical pencil. Dipping a pencil into honey, a person looks at the reaction: when it turns purple, one can conclude that the honey is not real.

Transaction costs permeate the entire sphere of economic life of society. We all face similar costs at every step, sometimes without realizing it. Scientists often compare transaction costs in economics and friction in physics, drawing an analogy between them. American economist D. Stigler wrote that “ the surrounding world with no transaction costs is as strange as the physical world with no friction forces" R. Coase argued that if all of the above types of transaction costs were suddenly absent, then nothing could interfere with the completion of transactions (transactions) and, as a result, eternity would be lived in a matter of fractions of a second. Exchange transactions would take place instantly, because not the slightest share of resources would be spent on searching for this or that information.

Among the costs that economic science deals with, we must distinguish between two types of costs:

- transformation costs (technology costs);

- transaction costs.

Transformation costs are the costs that accompany the process of physical change in a material, as a result of which we obtain a product that has a certain quality.

Transformation costs also include certain elements of measurement and planning. They are usually overlooked or referred to as transaction costs, when they may be pure technology.

Transaction costs are the costs that ensure the transfer of property rights from one hand to another and the protection of these rights. Unlike transformation costs, transaction costs are not associated with the value creation process itself.

Forms of transaction costs

Transaction costs (transaction costs -transactioncosts) — these are the costs in the sphere associated with the transfer. The category of transaction costs was introduced into economics in the 1930s. Ronald Coase and is now widely used. In his article “The Nature of the Firm,” he defined transaction costs as operating costs.

Let's consider the possible alternatives provided to us by everyday life. A typical example is apartment renovation. You can do it yourself if you know how and if you have an interest in it. Or you can organize the entire process, hiring workers on the market for each specific operation, purchasing paint and calculating how much it is needed, etc. In this case, you are trying to enter into a series of transactions that will be purely market and exclude your interaction with one company. After all You don’t trust the company in advance, believing that it has its own interests, and you will do the repairs cheaper. However, if you are a busy person or rich enough, you hire a company to renovate your apartment because your opportunity cost of time is higher than the cost you will spend organizing this process. Most often this is due to " wealth effect"-"wealth effect". This term was also first introduced by Coase. In his theory, the concept of “transaction costs” is opposed to the concept of “agency costs”, and the choice between one or another type of costs is largely determined by the “wealth effect”.

Currently, transaction costs are understood by the vast majority of scientists integrally, as the costs of system functioning. Transaction costs are the costs that arise when individuals exchange their property rights under conditions of incomplete information or confirm them under the same conditions. When people exchange property rights, they enter into a contractual relationship. When they confirm their ownership, they do not enter into any contractual relationship (they already have one), but they protect it from attacks by third parties. They are afraid that their property rights will be infringed by a third party, so they spend resources on protecting these rights (for example, building a fence, maintaining a police force, etc.).

There are usually five main forms of transaction costs:

- information search costs;

- costs of negotiations and contracts;

- measurement costs;

- costs of specification and protection of property rights;

- costs of opportunistic behavior.

Costs of searching for information are associated with its asymmetric distribution in the market: time and money have to be spent searching for potential buyers or sellers. Incompleteness of available information results in additional costs associated with the purchase of goods at prices above the equilibrium (or sale below the equilibrium), with losses arising from the purchase of substitute goods.

Negotiation and contracting costs also require an investment of time and resources. Costs associated with negotiations on the terms of sale and legal registration of the transaction often significantly increase the price of the item being sold.

A significant part of transaction costs are measurement costs, which is associated not only with direct costs for measuring equipment and the measurement process itself, but also with errors that inevitably arise in this process. In addition, for a number of goods and services, only indirect or ambiguous measurement is allowed. How, for example, can you evaluate the qualifications of a hired employee or the quality of a purchased car? Certain savings are determined by the standardization of manufactured products, as well as the guarantees provided by the company (free warranty repairs, the right to exchange defective products for good ones, etc.). However, these measures cannot completely eliminate measurement costs.

Particularly large costs of specification and protection of property rights. In a society where there is no reliable legal protection, cases of constant violation of rights are not uncommon. The time and cost required to restore them can be extremely high. This should also include the costs of maintaining judicial and government bodies that guard law and order.

Costs of opportunistic behavior are also associated with, although not limited to, information asymmetry. The fact is that post-contract behavior is very difficult to predict. Dishonest individuals will fulfill the terms of the contract to the minimum or even evade their fulfillment (if sanctions are not provided). Such moral hazard always exists. It is especially great in conditions of joint work - working as a team, when the contribution of everyone cannot be clearly separated from the efforts of other team members, especially if the potential capabilities of each are completely unknown. So, opportunistic refers to the behavior of an individual who evades the terms of a contract in order to make a profit at the expense of partners. It can take the form of extortion or blackmail when the role of those team members who cannot be replaced by others becomes apparent. Using their relative advantages, such team members can demand special working conditions or pay for themselves, blackmailing others with the threat of leaving the team.

Thus, transaction costs arise before the exchange process (ex ante), during the exchange process and after it (ex post). The deepening division of labor and the development of specialization contribute to the growth of transaction costs. Their size also depends on the form of ownership dominant in society. There are three main forms of ownership: private, common (communal) and state. Let us consider them from the point of view of the theory of transaction costs.

Paul R. Milgrom and John Roberts proposed the following classification of transaction costs. They divide them into two categories: costs associated with coordination and costs associated with motivation.

Coordination costs:- Cost of determining contract details- market survey to determine what can be bought on the market.

- Contract Definition Costs— studying the conditions of partners who supply the necessary services or goods.

- Costs of direct coordination— the need to create a structure within which the parties are brought together.

- Costs associated with incomplete information. Limited information about the market can lead to refusal to complete a transaction (purchase of a good). This is due to the fact that the level of uncertainty can become so high that people prefer to abandon the transaction rather than spend energy on obtaining additional information.

- Costs of opportunism. These costs are associated with overcoming possible opportunistic behavior, with overcoming the partner’s dishonesty towards you, and lead to the fact that you hire a supervisor, or try to find and include in the contract some additional measures of your partner’s effectiveness.

O. Williamson tried to evaluate all transactions by frequency of transactions and specificity of assets.

1. One-time or elementary exchange on an anonymous market.

An example of a one-time purchase would be the purchase of a teapot at the market. Having bought one kettle, you will buy the next one only when this one breaks. In this case, there are no specific assets, but the point is that the seller does not care who he sells the kettle to. The only determining criterion here is the price.

2. Repeated exchange of bulk goods.

There is still no asset specificity. For example, by constantly buying bread from the same seller, you know that it is of good quality, and therefore do not spend money on additional evaluation of whether they sold you good bread, what kind of bread is available in other bakeries, etc. This is very important, because thereby you save significantly on search costs, on the costs of measuring the quality of bread, and your behavior gives the seller greater confidence in turnover (that he will sell the bread).

3. A recurring contract related to investments in specific assets.

What are "specific assets"? A specific asset is always created for a specific transaction. Let's say I built a building for use as a workshop. I can, of course, use it alternatively, but then I will suffer losses. Those. even the next best opportunity to use that asset has a much lower return and is associated with risk. Specific assets are such costs, the next use of which is much less profitable.

4. Investments in idosyncratic (unique, exclusive) assets.

Idiosyncratic asset is an asset that, when used alternatively (when removed from a given transaction), loses value altogether, or its value becomes negligible. These assets include half of production investments—investments in a specific technological process. For example, a built blast furnace can no longer be used except for its intended purpose. Even if climbing competitions are held on it, it will not cover even 1% of the costs of its construction. In this case, the asset is idiosyncratic, i.e. tied to a specific technology.

The concept of transaction costs was introduced by R. Coase in the 1930s in his article “The Nature of the Firm.” It has been used to explain the existence of hierarchical structures that are antithetical to the market, such as firms. R. Coase associated the formation of these “islands of consciousness” with their relative advantages in terms of saving on transaction costs. He saw the specifics of the company's functioning in the suppression of the price mechanism and its replacement with a system of internal administrative control.

Transaction or transaction costs are the costs in the sphere of exchange associated with the transfer of property rights. There are usually five main forms of transaction costs:

1. costs of searching for information;

2. costs of negotiating and concluding contracts;

3. measurement costs;

4. costs of specification and protection of property rights;

5. costs of opportunistic behavior.

The most famous domestic typology of transaction costs is the classification proposed by R. Kapelyushnikov.

1. Costs of searching for information. Before a transaction is made or a contract is concluded, you need to have information about where you can find potential buyers and sellers of the relevant goods and factors of production, and what the current prices are. Costs of this kind consist of the time and resources required to conduct the search, as well as losses associated with the incompleteness and imperfection of the acquired information.

2. Negotiation costs. The market requires the diversion of significant funds for negotiations on the terms of exchange, for the conclusion and execution of contracts. The main tool for saving this kind of costs is standard (standard) contracts.

3. Measurement costs. Any product or service is a set of characteristics. In the act of exchange, only some of them are inevitably taken into account, and the accuracy of their assessment (measurement) can be extremely approximate. Sometimes the qualities of a product of interest are generally immeasurable, and to evaluate them one has to use surrogates (for example, judging the taste of apples by their color). This includes costs for the appropriate measuring equipment, for carrying out the measurement itself, for implementing measures aimed at protecting the parties from measurement errors and, finally, losses from these errors. Measurement costs increase with increasing accuracy requirements.

Enormous savings in measurement costs have been achieved by mankind as a result of the invention of standards for weights and measures. In addition, the goal of saving these costs is determined by such forms of business practices as warranty repairs, branded labels, purchasing batches of goods based on samples, etc.

4. Costs of specification and protection of property rights. This category includes the costs of maintaining courts, arbitration, government bodies, the cost of time and resources necessary to restore violated rights, as well as losses from their poor specification and unreliable protection. Some authors (D. North) add here the costs of maintaining a consensus ideology in society, since educating members of society in the spirit of observing generally accepted unwritten rules and ethical standards is a much more economical way to protect property rights than formalized legal control. In D. North’s interpretation, transaction costs “consist of the costs of assessing the useful properties of the object of exchange and the costs of ensuring rights and enforcement of their observance.” These costs inform social, political, and economic institutions.

5. Costs of opportunistic behavior. This is the most hidden and, from the point of view of economic theory, the most interesting element of transaction costs. There are two main forms of opportunistic behavior.

The first is called “moral hazard”. Moral hazard occurs when one party to a contract relies on the other, and obtaining actual information about the subject's behavior is costly or impossible. The most common type of opportunistic behavior of this kind is shirking, when the agent works with less efficiency than is required of him under the contract.

The second is the so-called “extortion” (hold-up). Take, for example, a worker who has acquired some unique skills over many years of cooperation with the same company. On the one hand, in any other position his qualifications and skills would be of less value, which means his wages would be lower. On the other hand, the company receives greater returns from him than from any newcomer who is not familiar with the specifics of its activities. The worker and the firm become to a certain extent indispensable, “mutually specialized” in relation to each other. Under conditions of a bilateral monopoly, when none of the participants can find an adequate replacement on the market, additional net income arises - quasi-rent, which must somehow be divided between them. But it exists only as long as the cooperation lasts. Termination or non-resumption of the transaction threatens the complete loss of capital embodied in special assets.

This creates the ground for “extortion.” Each partner has the opportunity to blackmail the other by threatening to break off business relations with him. For example, a company may threaten an experienced worker with dismissal if he does not agree to a wage reduction. The landowner can blackmail the company that built the plant on his land by terminating the lease agreement. The purpose of such extortion is the appropriation of all quasi-rent or, at least, a sharp increase in one’s share in it.

The category of “transactions” covers both the material and contractual aspects of the exchange. It is understood extremely broadly and is used to refer to both the exchange of goods and various types of activities, and the exchange of legal obligations of long-term or short-term transactions, both requiring detailed documentation and involving a simple mutual understanding of the parties.

In order for a transaction to take place, it is necessary to collect information about the prices and quality of goods and services, agree on its terms, monitor the integrity of its implementation by the partner, and if she is still upset due to his fault, then in this case, in order to achieve compensation, it may be necessary put in a lot of effort. Therefore, transactions may require significant costs and be accompanied by serious losses. These costs are called “transaction” costs. They are the main factor determining the structure and dynamics of various social institutions.

The introduction of the concept of transaction costs into economic analysis was a major theoretical achievement. Recognition of the “non-free” nature of the very process of interaction between people made it possible to shed light on the nature of economic reality in a completely new way: “Without the concept of transaction costs, which is largely absent in modern economic theory, it is impossible to understand how the economic system works, to productively analyze a whole range of emerging problems, and also provide a basis for developing policy recommendations.”

Even a simple listing of the available definitions says a lot about its content: “the costs of exchanging property rights,” “the costs of implementing and protecting contracts,” “the costs of obtaining benefits from specialization and division of labor,” “the costs of coordinating and motivating the activities of economic agents.”

In other words, transaction costs could be defined as the costs of economic interaction, no matter what forms it takes: “Transaction costs cover the costs of making decisions, developing plans and organizing future activities, negotiating about its content and conditions - when two people enter into a business relationship or more participants. Costs of changing plans, revising the terms of the transaction and resolving controversial issues when this is dictated by changed circumstances; the costs of ensuring that participants comply with the agreements reached. Transaction costs also include any losses arising from the ineffectiveness of joint decisions, plans, concluded contracts and created structures; ineffective responses to changed conditions; ineffective protection of agreements. In a word, they include everything that, one way or another, is reflected in the comparative performance of various methods of allocating resources and organizing production activities.”

The category of transaction costs originates from two works by R. Coase - “The Nature of the Firm” (1937) and “The Problem of Social Costs” (1960). Coase himself initially attributed to them only the costs that arise when using the price market mechanism. Later, they began to include costs associated with the use of administrative control mechanisms. With such an expanded interpretation, the concept of transactions is permissible both for the relationships that develop between organizations and for the relationships that develop within them.

Part of the transaction costs, which can be considered preliminary, relates to the moment before the transaction (collection of information), the other occurs at the time of its execution (negotiations and conclusion of the contract), the third is of a post-contractual nature (security measures against opportunistic behavior, measures to restore violated property rights ).

Transaction costs can appear in explicit or implicit form. If they are so large that they completely block the possibility of a transaction, then they cannot be registered (since no transactions are made). But this does not make their impact any less real: after all, it is their excessively high potential level that forces economic agents to refuse inclusion in the exchange process. Thus, the total costs of society are made up of the costs of land, labor, capital and entrepreneurial ability.

Necessary, firstly, to transform the physical properties of various goods: their color, chemical composition, location, etc., and secondly, to establish interaction between the economic agents themselves (delimitation, protection, transfer and unification of property rights). If the level of “transformation” costs (as D. North called them) is determined primarily by technological factors, then the level of transaction costs is determined by institutional ones. As K. Arrow aptly puts it, transaction costs are “the costs of keeping economic systems running.”

Of course, this does not mean that these and other costs can be considered in isolation, without the existing relationship between them. For example, high transaction costs often predetermine the choice of production methods. (Thus, the blurring of property rights can lead to a refusal to invest in long-term assets and the predominance of labor-intensive technologies.) And, conversely, the emergence of new technologies can complicate or simplify the process of concluding transactions, leading to a reduction or increase in the costs associated with them.

One of the most important features of transaction costs is that they allow for significant economies of scale. There are constant components in all types of transaction costs: once information is collected, it can be used by any number of potential sellers and buyers; contracts are standardized; the cost of developing legislation or administrative procedures depends little on how many people are subject to them.

The role of transaction costs in the economic world, as noted above, is often compared with the role of friction in the physical world: “Just as friction interferes with the movement of physical objects by dissipating energy in the form of heat, so transaction costs prevent the movement of resources to users for whom they represent the greatest value, dispersing the usefulness of these resources throughout the economic process. Just as every known physical object is given a form that helps either minimize friction or obtain some useful effect from it (a wheel, for example, serves both). In fact, any institution known to us arises as a reaction to the presence of transaction costs and in order, apparently, to minimize their impact, thereby increasing the benefits of exchange.