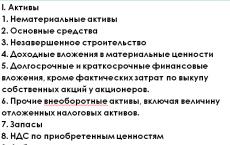

The story of Ivan Kulibin. Russian inventor Ivan Kulibin (biography, inventions). Why was this device so interesting?

Kulibin Ivan Petrovich (1735-1818), mechanic, inventor.

Having learned literacy and arithmetic from a deacon, Kulibin independently studied mechanics and opened a watch workshop.

In 1764-1769. he made an egg-shaped clock in which a theatrical action was played out every hour. The inventor presented them to Catherine II, who arrived in Nizhny Novgorod, and was appointed head of the mechanical workshops of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

Having moved to the capital, Kulibin in 1769-1787. served as a mechanic and supervised workshops.

In the 70s. 18th century he designed a wooden single-arch bridge across the Neva with a span of 298 m (instead of 50-60 m). A life-size model of the bridge was tested by a special academic commission, but the bridge was not built.

From 1791, Kulibin worked on options for a metal bridge, but the government rejected this project as well.

For unknown reasons, Kulibin did not have a relationship with Princess E. R. Dashkova, the president of the Academy of Sciences and the Academy of the Russian Language.

Freed in 1787 from managing workshops, Kulibin devoted himself entirely to invention: he designed a lantern with a reflector, a “lifting chair” (elevator), a three-wheeled pedal cart, an optical telegraph, “mechanical legs” (prostheses), and tried to create a perpetual motion machine.

In 1792 he was elected a member of the Free Economic Society.

In 1801, Kulibin retired and returned to Nizhny Novgorod, where until the end of his life he was engaged in drafting ships with a machine engine.

He also invented many other things: a device for boring the inner surfaces of cylinders, a machine for extracting salt, seeders, a mill machine, a water wheel of a special design, etc.

But most of them were not in demand, and last years Kulibin lived in great need.

Ivan Petrovich Kulibin (1735-1818)

Russian self-taught mechanic, inventor

Ivan Petrovich was born in Nizhny Novgorod on April 21, 1735, in the family of a poor flour merchant.

Kulibin's father did not give his son a school education, he taught him to trade. He studied with a deacon, and in free time made weather vanes, gears. Everything related to technology worried him greatly, the young man was especially interested in mills and watch mechanisms.

Once Kulibin was sent to Moscow, this trip gave him the opportunity to get acquainted with watchmaking, to purchase tools. Upon his return from Moscow, he opened a watchmaking workshop and began to excel in watchmaking.

Kulibin decided to create a complex watch.

This clock was the size of a goose egg. They consisted of a thousand smallest details, wound up once a day and beat off the allotted time, even half and a quarter.

At the time of the invention of watches, Kulibin was not only a watchmaker, but also a locksmith, toolmaker, metal and wood turner, besides, a designer and technologist. He was even a composer - the clock played a melody composed by him. The mechanic spent more than 2 years to make this wonderful watch.

On May 20, 1767, Empress Catherine II arrived in Nizhny Novgorod. Kulibin presented the clock to the tsarina, as well as those he created: an electric machine, a telescope, a microscope. The queen praised the talent of the inventor.

In 1769, Ivan Petrovich was summoned by the Empress to St. Petersburg and appointed head of the mechanical workshop of the Academy of Sciences with the title of mechanic. And his inventions ended up in the Kunstkamera - a kind of museum established by Peter the Great.

In St. Petersburg, he managed workshops with numerous departments (tool, turning, carpentry, barometric, optical), but he also found time to develop his own inventions.

He designed a wooden single-arch bridge across the Neva.

The commission recognized that it is possible to build according to the Kulibin project. Catherine II ordered to award Kulibin with money and a gold medal. But no one was going to build a bridge.

Kulibin also invented an original lamp, which can be considered a prototype of a modern searchlight.

For this lamp, he used a concave mirror, consisting of a huge number of individual pieces of mirror glass. A light source was placed at the focus of the mirror, the strength of which was increased by a factor of 500 by the mirror.He invented lanterns of different sizes and strengths: some were convenient for lighting corridors, large workshops, ships, were indispensable for sailors, while others, smaller in size, were suitable for carriages.

Another invention is a powered watercraft. For the built ship, Kulibin was awarded five thousand rubles, but his ship was never put into operation.

Kulibin spent money on the creation of new inventions.

In 1791, Kulibin created a three-wheeled scooter.

In the same year, Kulibin designed mechanical legs (prosthesis). Military surgeons recognized the prosthesis invented by Kulibin as the most perfect of all those that existed at that time.

Kulibin developed both a telegraph of an original design and a secret telegraph code. But this idea was not appreciated.

The last dream of the inventor was a perpetual motion machine.

Kulibin died, surrounded by blueprints, working to his last breath. In order to bury him, the wall clock had to be sold. There was not a penny in the inventor's house. He lived and died a beggar.

Ivan Petrovich Kulibin is an outstanding Russian mechanic-inventor of the 18th century. His surname has become a household name, "kulibins" are now called self-taught masters.

Ivan Kulibin became the prototype of the self-taught watchmaker Kuligin - the hero of the play "Thunderstorm" by Alexander Ostrovsky.Ivan Petrovich Kulibin was born on April 10 (21 according to a new style) in 1735 in the village of Podnovye, Nizhny Novgorod district (now this village is part of Nizhny Novgorod) in the family of an Old Believer merchant. Ivan Kulibin kept loyalty to the traditions of the Old Believers all his life: he never smoked tobacco, did not play cards, did not drink alcohol. When Catherine II offered Kulibin to shave off his full beard in exchange for receiving the nobility, Kulibin preferred to remain in the merchant class with a beard.

Ivan Kulibin learned flour trading from childhood, but he was more attracted to various mechanisms, such as bell clocks. Kulibin independently studied mechanics from books, including the works of Mikhail Lomonosov. From the age of 17, Kulibin began to make handicrafts for home and for sale: wooden and copper cuckoo clocks, wooden circles for casting copper wheels, lathe and other tools. An acquaintance of his father, also an Old Believer merchant Kostromin, drew attention to Kulibin's talent. He gave Kulibin money to make unusual watches to present them to Empress Catherine II. Along with the manufacture of watches for the Empress, Kulibin made an electric machine and a microscope. Finally, on April 1, 1769, Kulibin and Kostromin appeared before Catherine II with a miracle watch. The clock was shaped like an egg, in which small doors opened every hour. Behind them was the Holy Sepulcher, on the sides of the Sepulcher stood two guards with spears. The angel rolled away the stone from the Tomb, the guards fell on their faces, two myrrh-bearing women appeared; the chimes played three times "Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death and bestowing life on those in the tombs" and the doors were closed. From five in the evening until eight in the morning, another verse was already playing: "Jesus is risen from the tomb, as if he had prophesied, give us eternal life and great mercy." The clock mechanism consisted of more than 1000 tiny wheels and other mechanical parts, while the watch was only the size of a duck or goose egg.

After this presentation of home-made miracle watches, Empress Catherine appointed Ivan Kulibin the head of the mechanical workshop of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. For 17 years, Kulibin directed the workshops of the Academy and brought to life his new inventions: a 300-meter single-arch bridge across the Neva with wooden lattice trusses, a searchlight, a mechanical crew with a pedal drive, "mechanical legs" (prostheses), an elevator, a river boat with a water-acting an engine moving against the current, an optical telegraph, a salt mining machine, a device for boring and processing the inner surface of cylinders, and much more.

The Peacock clock was created in the 18th century by the English master James Cox and purchased by Prince Potemkin in disassembled form. The only person in Russia who managed to assemble this watch was Ivan Kulibin. The Peacock clock is still working and is one of the most interesting exhibits of the Hermitage.

Kulibin was married three times, the third time he married a 70-year-old man, and the third wife bore him three daughters. In total, he had 11 children of both sexes.

At the end of his life, Ivan Kulibin became interested in creating a perpetual motion machine and, having spent all his savings on an unrealizable dream, died in poverty on July 30 (August 11, according to a new style), 1818 in Nizhny Novgorod. To raise money for his funeral, Kulibin's widow sold the only wall clock left in the house.

site is an information-entertainment-educational site for all ages and categories of Internet users. Here, both children and adults will have a good time, they will be able to improve their level of education, read interesting biographies of great and famous people in different eras, watch photographs and videos from the private sphere and public life popular and eminent personalities. Biographies of talented actors, politicians, scientists, pioneers. We will present you with creativity, artists and poets, music of brilliant composers and songs of famous performers. Screenwriters, directors, astronauts, nuclear physicists, biologists, athletes - a lot of worthy people who have left an imprint on time, history and the development of mankind are brought together on our pages.

On the site you will learn little-known information from the fate of celebrities; fresh news from cultural and scientific activities, family and personal life of stars; reliable facts of the biography of prominent inhabitants of the planet. All information is conveniently organized. The material is presented in a simple and clear, easy to read and interestingly designed form. We have tried to ensure that our visitors receive the necessary information here with pleasure and great interest.

When you want to find out details from the biography of famous people, you often start looking for information from many reference books and articles scattered all over the Internet. Now, for your convenience, all the facts and the most complete information from the life of interesting and public people are collected in one place.

the site will tell in detail about the biography famous people left their imprint in human history, both in ancient times and in our modern world. Here you can learn more about the life, work, habits, environment and family of your favorite idol. About the success stories of bright and extraordinary people. About great scientists and politicians. Schoolchildren and students will draw on our resource the necessary and relevant material from the biography of great people for various reports, essays and term papers.

Finding out the biographies of interesting people who have earned the recognition of mankind is often a very exciting activity, since the stories of their destinies capture no less than others. works of art. For some, such reading can serve as a strong impetus for their own accomplishments, give confidence in themselves, and help them cope with a difficult situation. There are even statements that when studying the success stories of other people, in addition to motivation for action, leadership qualities are also manifested in a person, strength of mind and perseverance in achieving goals are strengthened.

It is also interesting to read the biographies of rich people posted with us, whose perseverance on the path to success is worthy of imitation and respect. Big names of past centuries and present days will always arouse the curiosity of historians and ordinary people. And we set ourselves the goal of satisfying this interest to the fullest extent. Do you want to show off your erudition, prepare thematic material, or are you just interested in learning everything about historical figure- go to the site.

Fans of reading people's biographies can learn from their life experience, learn from someone else's mistakes, compare themselves with poets, artists, scientists, draw important conclusions for themselves, and improve themselves using the experience of an extraordinary personality.

By studying the biographies of successful people, the reader will learn how great discoveries and achievements were made that gave humanity a chance to ascend to a new stage in its development. What obstacles and difficulties had to overcome many famous people arts or scientists, famous doctors and researchers, businessmen and rulers.

And how exciting it is to plunge into the life story of a traveler or discoverer, imagine yourself as a commander or a poor artist, learn the love story of a great ruler and get to know the family of an old idol.

The biographies of interesting people on our site are conveniently structured so that visitors can easily find information about any person they need in the database. Our team strived to ensure that you like both simple, intuitive navigation, and easy, interesting style of writing articles, and original page design.

Everyone knows that Kulibin is a great Russian inventor, mechanic, engineer. His surname has long become a common noun in Russian. But, as a recent survey showed, only five percent of respondents can name at least one of his inventions. How so? We decided to conduct a small educational program: so, what did Ivan Petrovich Kulibin invent?

Despite the fact that not a single serious invention of Kulibin was truly appreciated, he was much more fortunate than other Russian self-taught, who were either not allowed even at the Academy of Sciences, or went home with a 100-ruble bonus and a recommendation not to climb again. not in your business.

Ivan Petrovich, who was born in the Podnovye settlement near Nizhny Novgorod in 1735, was an incredibly talented person. Mechanics, engineering, watchmaking, shipbuilding - everything was argued in the capable hands of a self-taught Russian. He was successful and was close to the empress, but at the same time, none of his projects that could make life easier for ordinary people and promote progress was neither properly funded nor implemented by the state. While entertaining mechanisms - funny automatons, palace clocks, self-propelled guns - were financed with great joy.

shipping vessel

At the end of the 18th century, the most common way to lift cargo on ships against the current was barge work - hard, but relatively inexpensive. There were also alternatives: for example, machine ships driven by oxen. The device of the machine ship was as follows: it had two anchors, the ropes of which were attached to a special shaft. One of the anchors on a boat or along the shore was brought forward 800–1000 m and fixed. The oxen working on the ship rotated the shaft and wound the anchor rope, pulling the ship to the anchor against the current. At the same time, another boat was carrying a second anchor forward - this ensured the continuity of movement.

Kulibin came up with the idea of how to do without oxen. His idea was to use two paddle wheels. The current, turning the wheels, transferred energy to the shaft - the anchor rope was wound, and the ship pulled itself to the anchor using the energy of the water. In the process of work, Kulibin was constantly distracted by orders for toys for the royal offspring, but he managed to get funding for the manufacture and installation of his system on a small ship. In 1782, loaded with almost 65 tons (!) of sand, it proved to be reliable and much faster than a ship powered by an ox or barge haul.

In 1804, in Nizhny Novgorod, Kulibin built a second waterway, which was twice as fast as the burlatsky bark. Nevertheless, the Department of Water Communications under Alexander I rejected the idea and banned funding - the waterways never became widespread. Much later, capstans appeared in Europe and the USA - ships that pulled themselves to the anchor using the energy of a steam engine.

screw elevator

The most common lift system today is the cab with winches. Winch lifts were created long before the Otis patents of the mid-19th century - similar designs were in operation as far back as Ancient Egypt, they were set in motion by draft animals or slave power.

In the mid-1790s, the aging and overweight Catherine II instructed Kulibin to develop a convenient elevator for moving between the floors of the Winter Palace. She certainly wanted an elevator chair, and Kulibin faced an interesting technical challenge. It was impossible to attach a winch to such an elevator, open from above, and if the chair was “picked up” by a winch from below, it would cause inconvenience to the passenger. Kulibin solved the problem witty: the base of the chair was attached to a long axis-screw and moved along it like a nut. Catherine sat on her mobile throne, the servant twisted the handle, the rotation was transmitted to the axis, and she raised the chair to the second floor gallery. The Kulibin screw elevator was completed in 1793, and Elisha Otis built the second such mechanism in history in New York only in 1859. After the death of Catherine, the elevator was used by the courtiers for entertainment, and then was bricked up. To date, the drawings and remains of the lifting mechanism have been preserved.

The famous single-span bridge across the Neva - what it might look like if it was built. Kulibin performed his calculation on models, including those on a scale of 1:10.

The famous single-span bridge across the Neva - what it might look like if it was built. Kulibin performed his calculation on models, including those on a scale of 1:10.

Theory and practice of bridge building

From the 1770s until the early 1800s, Kulibin worked on the creation of a single-span stationary bridge across the Neva. He made a working model, on which he calculated the forces and stresses in various parts of the bridge - despite the fact that the theory of bridge building did not exist at that time! Empirically, Kulibin predicted and formulated a number of laws of sopromat, which were confirmed much later. At first, the inventor developed the bridge at his own expense, but Count Potemkin gave him money for the final layout. The 1:10 scale model reached a length of 30 m.

All bridge calculations were presented to the Academy of Sciences and verified by the famous mathematician Leonhard Euler. It turned out that the calculations were correct, and tests of the model showed that the bridge has a huge margin of safety; its height allowed sailing ships to pass without any special operations. Despite the Academy's approval, the government never provided funds for the construction of the bridge. Kulibin was awarded a medal and received a prize, by 1804 the third model had completely rotted away, and the first permanent bridge across the Neva (Blagoveshchensky) was built only in 1850.

In the 1810s, Kulibin was engaged in the development of iron bridges. Before us is a project of a three-arch bridge across the Neva with a suspended carriageway (1814). Later, the inventor created a project for a more complex four-arch bridge.

In the 1810s, Kulibin was engaged in the development of iron bridges. Before us is a project of a three-arch bridge across the Neva with a suspended carriageway (1814). Later, the inventor created a project for a more complex four-arch bridge.

In 1936, an experimental calculation of the Kulibino bridge was carried out using modern methods, and it turned out that the Russian self-taught did not make a single mistake, although in his time most of the laws of sopromat were unknown. The technique of manufacturing a model and testing it for the purpose of force calculation of the bridge structure subsequently became widespread, to which different time various engineers came independently. Kulibin was also the first to propose the use of lattice trusses in the construction of the bridge - 30 years before the American architect Itiel Town, who patented this system.

What else did Kulibin do?

- Established the work of workshops at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, where he was engaged in the manufacture of microscopes, barometers, thermometers, spyglasses, balances, telescopes and many other laboratory instruments. — Repaired the planetarium of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. - I came up with an original system for launching ships into the water. - Created the first optical telegraph in Russia (1794), sent to the Kunst Chamber as a curiosity. — Developed the first iron bridge project in Russia (across the Volga). — Designed an ordinary seeder that provides uniform sowing (was not built). - Arranged fireworks, created mechanical toys and automatons for the entertainment of the nobility. — I repaired and independently assembled many clocks of different layouts — wall, floor, tower.

On the bridge across the Neva

Despite the fact that not a single serious invention of Kulibin was truly appreciated, he was much more fortunate than many other Russian self-taught, who were either not allowed even on the threshold of the Academy of Sciences, or were sent home with a 100 ruble bonus and a recommendation no more mind your own business.

Common surnames

The surname Kulibina has become a household name in the meaning of "jack of all trades." This is not a unique case: the words "pullman", "diesel", "raglan", "whatman" and others also came from proper names. Most often, the invention was simply named after the inventor, but Kulibin's surname was made a household name by popular rumor. We have collected several more similar stories.

The word "boycott" comes from the name of the British captain Charles Boycott (1832-1897), who was the manager of the Irish lands of the large landowner Lord Erne. In 1880, Irish laborers refused to work for Boycott because of dog lease terms. Boycott's struggle with the strikers led to the fact that people began to ignore the manager, as if he did not exist at all: he was not served in stores, they did not talk to him. This phenomenon is called "boycott".

The word "silhouette" appeared due to the appointment of Etienne de Silhouette (1709−1767) to the post of Controller General (Minister) of Finance of France. He became a minister after the Seven Years' War, which plunged France into a crisis. Silhouette was forced to tax almost every sign of wealth, from expensive curtains to servants, and the wealthy camouflaged their fortunes by buying cheap things. Household items that mask wealth began to be called things-silhouettes, and in the middle of the 19th century, the simplest and cheapest kind of painting, outline along the contour, received this name.

The word "hooligan" appeared in London police reports in 1894 when describing youth gangs operating in the Lambeth area. They were called the Hooligan Boys, by analogy with the London thief Patrick Hooligan, already known to the police. The press picked up the word and elevated it to the rank of a whole phenomenon called hooliganism (hooliganism).

Self-running carriage and other stories

Often, Kulibin, in addition to the designs he actually invented, is credited with many others that he really improved, but was not the first. For example, Kulibin is often credited with the invention of a pedal scooter (a prototype of a velomobile), while another self-taught Russian engineer created such a system 40 years earlier, and Kulibin was the second. Let's look at some of the common misconceptions.

Kulibin's self-running stroller was distinguished by a complex drive system and required considerable effort from the driver. It was the second velomobile in history.

Kulibin's self-running stroller was distinguished by a complex drive system and required considerable effort from the driver. It was the second velomobile in history.

So, in 1791, Kulibin built and presented to the Academy of Sciences a self-propelled carriage, a “self-running carriage”, which was essentially the forerunner of a velomobile. It was designed for one passenger, and the car was set in motion by a servant standing on his heels and alternately pressing on the pedals. The self-running carriage served as an attraction for the nobility for some time, and then was lost in history; only her drawings have survived. Kulibin was not the inventor of the velomobile - 40 years before him, another self-taught inventor Leonty Shamshurenkov (known in particular for developing the lifting system of the Tsar Bell, which was never used for its intended purpose) built a self-running stroller similar in design in St. Petersburg. Shamshurenkov's design was double, in later drawings the inventor planned to build a self-propelled sled with a verstometer (a prototype of a speedometer), but, alas, did not receive proper funding. Like Kulibin's scooter, Shamshurenkov's scooter has not survived to this day.

The famous egg clock made by Kulibin in 1764-1767 and presented to Catherine II for Easter 1769. Largely thanks to this gift, Kulibin headed the workshops at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Now kept in the Hermitage.

The famous egg clock made by Kulibin in 1764-1767 and presented to Catherine II for Easter 1769. Largely thanks to this gift, Kulibin headed the workshops at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Now kept in the Hermitage.

Prosthetic leg

At the turn of the XVIII-XIX centuries. Ekov Kulibin presented several projects of "mechanical legs" to the St. Petersburg Medical-Surgical Academy - very advanced lower limb prostheses for those times, capable of simulating a leg lost above the knee (!) The “test” of the first version of the prosthesis, made in 1791, was Sergei Vasilyevich Nepeitsyn, at that time a lieutenant who lost his leg during the assault on Ochakov. Subsequently, Nepeitsyn rose to the rank of major general and received the nickname Iron Leg from the soldiers; he led a full life, and not everyone guessed why the general limped a little. The prosthesis of the Kulibin system, despite the favorable reviews of St. Petersburg doctors headed by Professor Ivan Fedorovich Bush, was rejected by the military department, and mass production of mechanical prostheses imitating the shape of the leg later began in France.

The searchlight lamp, created in 1779, has remained a technical curiosity. In everyday life - as lamps on carriages - only its smaller versions were used.

The searchlight lamp, created in 1779, has remained a technical curiosity. In everyday life - as lamps on carriages - only its smaller versions were used.

spotlight

In 1779, Kulibin, who was fond of optical instruments, presented his invention, a searchlight, to the St. Petersburg public. Systems of reflective mirrors existed before him (in particular, they were used on lighthouses), but Kulibin's design was much closer to a modern searchlight: a single candle, reflected from mirror reflectors placed in a concave hemisphere, gave a strong and directed stream of light. The "Wonderful Lantern" was positively received by the Academy of Sciences, praised in the press, approved by the Empress, but remained only entertainment and was not used for street lighting, as Kulibin initially believed. The master himself subsequently made a number of searchlights for individual orders of shipowners, and also made a compact lantern for a carriage based on the same system - this brought him a certain income. The master was summed up by the lack of copyright protection - other craftsmen began to mass-produce the coach "Kulibin lanterns", which greatly depreciated the invention.