A project about a famous medieval monastery in Europe. Monastery buildings of the Middle Ages. The history of the place is amazing and varied.

Monasteries were the cultural centers of the Christian world in the Dark Ages. Monastic communities as part catholic church were quite rich by the standards of that time: they owned significant land, which they rented out to local peasants. Only monks could provide medical assistance and some protection from both barbarians and secular authorities. In the monasteries, learning and science also found refuge. In large cities, bishops represented ecclesiastical authority, but they always strove more for secular power than for the establishment of Christianity. Monasteries, not bishops, did the main work of spreading the Christian religion during the Dark Ages.

Cities have been familiar with the Christian faith since Roman times. In the III-V centuries, Christian communities existed in all major cities of the Western Roman Empire, especially from the moment when the decree of Emperor Constantine elevated Christianity to the rank of official religion. Things were different in the countryside. The village, conservative by nature, hardly abandoned the usual pagan beliefs and the deities that always helped the peasant in his labors. The raids of the barbarians, from which the peasants suffered first of all, hunger and general disorder awakened at the beginning of the Dark Ages the oldest superstitions against which the official Christian church was often powerless.

At this time, monasteries and holy hermits, leading an emphatically independent way of life, became a beacon and support for the rural inhabitants, who made up the majority of the then population of Western Europe. Where by personal example, where by the power of persuasion and miracles, they planted hope in the souls of ordinary people. In the conditions of the complete autocracy of the barbarian rulers, in an era of inhuman cruelties, monasteries turned out to be the only refuge of order. Strictly speaking, the reason for the rise of the Catholic Church, the reason why the Church began to assume the role of a secular ruler, should be sought precisely in the history of the Dark Ages.

At a time when kings enjoyed absolute power in their lands and even violated the laws of their ancestors, committing robbery and murder, the Christian religion turned out to be the only law, at least somewhat independent of royal arbitrariness. In the cities, bishops (primarily those who were appointed by the church rather than bought the bishop's chair for money) sought to limit the arbitrariness of secular authorities, entering into direct confrontation with the rulers. However, behind the back of the king or his vassal, most often stood military force which the bishop did not have. The history of the Dark Ages knows many examples of how kings and dukes brutally tortured recalcitrant church rulers, subjecting them to such tortures, next to which the mockery of the Romans over the Christians of the first centuries fades. One Frankish majordomo gouged out the eyes of a bishop in his city, forced him to walk on broken glass for several days, and then executed him.

Only the monasteries maintained relative independence from the secular authorities. Monks who declared their renunciation of worldly life did not pose a clear threat to the rulers, and therefore they were most often left alone. So in the Dark Ages, monasteries were islands of relative peace in the midst of a sea of human suffering. Very many of those who entered the monastery during the Dark Ages did so only in order to survive.

Independence from the world meant for the monks the need to independently produce everything they needed. The monastic economy developed under the protection of double walls - those that protected the possessions of the monastery, and those that were erected by faith. Even during the barbarian invasions, the conquerors rarely dared to touch the monasteries, fearing to quarrel with an unknown god. This respectful attitude continued later. So the outbuildings of the monastery - a barnyard, vegetable gardens, a stable, a smithy and other workshops - sometimes turned out to be the only ones in the whole district.

The spiritual power of the monastery was based on economic power. Only monks in the Dark Ages stocked food for a rainy day, only monks always had everything needed to make and repair meager agricultural implements. Mills, which spread to Europe only after the tenth century, also first appeared in monasteries. But even before the monastic farms grew to the size of large feudal estates, the communities were engaged in charity out of a sacred duty. Helping the needy was one of the primary items in the charter of any monastic community in the Dark Ages. This assistance was expressed both in the distribution of bread to the surrounding peasants in a famine year, and in the treatment of the sick, and in the organization of hospices. The monks preached the Christian faith among the semi-pagan local population - but they preached by deeds, as much as by words.

The monasteries were the custodians of knowledge - those grains of it that survived the fire of barbarian invasions and the formation of new kingdoms. Behind the monastery walls, educated people could find shelter, whose learning no one else needed. Thanks to the monastic scribes, a part of the handwritten works from the Roman period has been preserved. True, this was taken seriously only towards the end of the Dark Ages, when Charlemagne ordered to collect old books throughout the Frankish Empire and rewrite them. The collection of ancient manuscripts was also carried out by Irish monks who traveled throughout Europe.

Teacher and student

Obviously, only a small part of the ancient manuscripts that were once kept in monasteries reached the researchers of later centuries. The reason for this is the scribes themselves.

Parchment, which has been written on since ancient times, was expensive, and very little was produced during the Dark Ages. So, when a scribe had fallen into disrepair by one of the church fathers, he often took a well-preserved parchment with a “pagan” text and mercilessly scraped a poem or a philosophical treatise from the parchment in order to write down in its place a more valuable one, from his point of view. view, text. On some of these transcribed parchments, poorly scraped lines in Classical Latin can still be seen showing through the later text. Unfortunately, it is completely impossible to restore such erased works.

The monastic community in the Dark Ages provided the model for Christian society as it should have been. Inside the monastery walls there was no "neither Greek nor Jew" - all the monks were brothers to each other. There was no division into "clean" and "impure" occupations - each brother was engaged in what he had an inclination for, or in what was defined as obedience to him. The rejection of the joys of the flesh and worldly life fully corresponded to the mindset of the entire Christian world: one should have expected the second coming of Christ and the Last Judgment, at which everyone will be rewarded according to his merits.

On the other hand, the closed monastic world was a smaller copy of Christian Europe, deliberately limiting contacts with the outside world, managing in everyday life with the few that could be produced or grown on their own. The founders of the monastic communities sought to limit the contacts of the monks with the laity in order to protect the brothers from temptations - and the entire Christian world tried to communicate as little as possible with the "pagans", to draw as little as possible from the treasury of foreign knowledge and culture (it does not matter, Roman or Islamic world).

Joseph Anton von Koch (1768-1839) "The Monastery of San Francesco di Civitella in the Sabine Mountains". Italy, 1812Wood, oil. 34 x 46 cm.

State Hermitage. The building of the General Staff. Room 352.

Sounds of time

The fine tuning of monastic life would not have been possible without a multitude of sound signals, primarily the ringing of large and small bells. They called the monks to the services of the hours and to mass, informed them that it was time to go to the refectory, and regulated physical labor.

Guillaume Durant, Bishop of Menda, in the 13th century distinguished six types of bells: squilla in the refectory, cimballum in the cloister, nola in church choirs, nolula or dupla in the clock, campana in the bell tower, signum in the tower.

Miniature from the manuscript "Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung". Germany, around 1425. Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg

Depending on the tasks, the bells were rung in different ways. For example, when calling monks to the service of the first hour and to Compline, they struck once, and to the services of the third, sixth and ninth hours - three times. In addition, monasteries used wooden plank(tabula) - for example, they beat her to announce to the brethren that one of the monks was dying.

Schedule

Different abbeys had their own daily routine - depending on the day of the week, simple or holidays, etc. For example, in Cluny during the spring equinox, closer to Easter, the schedule could look like this (all references to astronomical hours are approximate):

About 00:30

First awakening; the monks gather for the vigil.

02:30

The brethren go back to sleep.

04:00

Matins.

04:30

They fall asleep again.

05:45-06:00

They rise again at dawn.

06:30

First canonical hour; after him, the monks from the church go to the chapter hall (readings from the charter or the Gospel; discussion of administrative issues; accusatory chapter: the monks confess their own violations and blame other brothers for them).

07:30

Morning mass.

08:15-09:00

Individual prayers.

09:00-10:30

Service of the third hour, followed by the main mass.

10:45-11:30

Physical work.

11:30

Sixth hour service.

12:00

Meal.

12:45-13:45

Afternoon rest.

14:00-14:30

Ninth hour service.

14:30-16:15

Work in the garden or in the scriptorium.

16:30-17:15

Vespers.

17:30-17:50

Light dinner (except fasting days).

18:00

Compline.

18:45

The brethren go to sleep.

IV. Monastery architecture

Benedict of Nursia, in his charter, prescribed that the monastery should be built as a closed and isolated space, allowing you to isolate yourself from the world and its temptations as much as possible:

“The monastery, if this is possible, should be arranged in such a way that everything necessary, that is, water, a mill, a fish tank, a vegetable garden and various crafts, are inside the monastery, so that there is no need for monks to go outside the walls, which does not at all serve the benefit of souls them".

If the architecture of the Romanesque and, even more so, the Gothic church, with its high windows and vaults directed to heaven, was often likened to a prayer in stone, then the layout of the monastery, with its premises intended only for monks, novices and converse, can be called discipline embodied in the walls. and galleries. A monastery is a closed world where dozens, and sometimes hundreds of men or women, must go together to salvation. This is a sacred space (the church was likened to Heavenly Jerusalem, the cloister was likened to the Garden of Eden, etc.) and at the same time a complex economic mechanism with barns, kitchens and workshops.

Of course, medieval abbeys were not built according to the same plan at all and were completely different from each other. An early medieval Irish monastery, where a dozen hermit brothers who practiced extreme asceticism lived in tiny stone cells, can hardly be compared with the huge abbey of Cluny in its heyday. There were several cloister courtyards (for monks, novices and the sick), separate chambers for the abbot and a giant basilica - the so-called. Church of Cluny III (1088-1130), which until the construction of the current St. Peter's Cathedral in Rome (1506-1626) was the largest church in the Catholic world. The monasteries of the mendicant orders (primarily the Franciscans and Dominicans, which were usually built in the middle of the cities where the brothers went to preach) are not at all like the Benedictine cloisters. The latter were often erected in forests or on mountain cliffs, like Mont Saint-Michel on a rocky islet off the coast of Normandy or Sacra di San Michele in Piedmont (this abbey became the prototype of the Alpine monastery described in Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose).

The architecture of the monastery churches and the arrangement of the entire abbey, of course, depended on local traditions available building materials, the size of the brotherhood and its financial capabilities. However, it was also important how open the monastery was to the world. For example, if a monastery, thanks to the relics or miraculous images stored there, attracted a lot of pilgrims (like the Abbey of Sainte-Foy in Conques, France), it was necessary to equip the infrastructure for their reception: for example, to expand and rebuild the temple so that pilgrims could access the desired shrines and did not pass each other, to build hospitable houses.

The oldest and most famous of the medieval monastic plans was drawn up in the first half of the ninth century in the German abbey of Reichenau for Gosbert, abbot of St. Gallen (in modern Switzerland). Five sheets of parchment (with a total size of 112 × 77.5 cm) depict not a real, but an ideal monastery. This is a huge complex with dozens of buildings and 333 inscriptions that indicate the names and purpose of various buildings: churches, scriptorium, dormitory, refectory, kitchens, bakery, brewery, abbot's residence, hospital, houses for guest monks, etc.

We will choose a simpler plan, which shows how a typical Cistercian monastery, similar to the abbey of Fontenay, founded in Burgundy in 1118, could be arranged in the 12th century. Since the structure of the Cistercian abbeys largely followed older models, this plan has much to say about life in the monasteries and other Benedictine "families".

Model monastery

1. Church

2. Cloister

3. Washbasin

4. Sacristy

5. Library

6. Chapter Hall

7. Room for conversations

8. Bedroom

9. Warm room

10. Refectory

11. Kitchen

12. Refectory for converse

13. Entrance to the monastery

14. Hospital

15. Other buildings

16. Large pantry

17. Converse corridor

18. Cemetery

1. Church

Unlike the Cluniacs, the Cistercians strove for maximum simplicity and asceticism of form. They abandoned the crowns of chapels in favor of a flat apse and almost completely expelled figurative decor from the interiors (statues of saints, stained-glass windows, scenes carved on capitals). In their churches, which were supposed to conform to the ideal of severe asceticism, geometry triumphed.

Like the vast majority of Catholic churches of that time, the Cistercian churches were built in the form of a Latin cross (where the elongated nave was crossed at right angles by a transept), and their interior space was divided into several important zones.

At the eastern end was the presbytery (A), where the main altar stood, on which the priest celebrated Mass, and nearby in the chapels arranged in the arms of the transept, additional altars were placed.

The gate arranged on the north side of the transept (B), usually led to the monastery cemetery (18) . From the south side, which adjoined other monastic buildings, it was possible to (C) go up to the monastery bedroom - dormitory (8) , and next to it was a door (D) through which the monks entered and exited the cloister (2) .

Further, at the intersection of the nave with the transept, there were choirs (E). There the monks gathered for the services of the hours and for masses. In the choirs, opposite each other, there were two rows of benches or chairs (English stalls, French stalles) in parallel. In the late Middle Ages, reclining seats were most often made in them, so that monks during tedious services could either sit or stand, leaning on small consoles - misericords (recall the French word misericorde - "compassion", "mercy" - such shelves, indeed, were a mercy to the weary or infirm brothers).

Benches were placed behind the choir. (F) where, during the service, the sick brothers, temporarily separated from the healthy ones, as well as novices, were located. Next came the partition (English rood screen, French jubé), on which a large crucifix was installed (G). In parish churches, cathedrals and monastery churches, where pilgrims were admitted, it separated the choir and presbytery, where worship was held and the clergy were located, from the nave, where the laity had access. The laity could not go beyond this border and in fact did not see the priest, who, in addition, stood with his back to them. In modern times, most of these partitions were demolished, so when we enter some medieval temple, we need to imagine that earlier its space was not at all uniform and accessible to everyone.

In Cistercian churches in the nave there could be a choir for converse (H) worldly brothers. From their cloister they entered the temple through a special entrance (I). It was located near the western portal (J) through which the laity could enter the church.

2. Cloister

A quadrangular (more rarely, polygonal or even round) gallery, which adjoined the church from the south and connected the main monastic buildings together. A garden was often laid out in the center. In the monastic tradition, the cloister was likened to Eden surrounded by a wall, Noah's Ark, where the family of the righteous was saved from the waters sent to sinners as punishment, Solomon's temple or Heavenly Jerusalem. The name of the galleries comes from the Latin claustrum - "enclosed, enclosed space." Therefore, in the Middle Ages, both the central courtyard and the entire monastery could be called that.

The cloister served as the center of monastic life: along its galleries, the monks moved from the bedroom to the church, from the church to the refectory, and from the refectory, for example, to the scriptorium. There was a well and a place for washing - lavatorium (3) .

Solemn processions were also held in the cloister: for example, in Cluny every Sunday between the third hour and the main mass, the brothers, led by one of the priests, marched through the monastery, sprinkling all the rooms with holy water.

In many Benedictine monasteries, such as the abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos (Spain) or Saint-Pierre-de-Moissac (France), many scenes from the Bible, lives of saints, allegorical images (as a confrontation between vices and virtues), as well as frightening figures of demons and various monsters, animals woven together, etc. The Cistercians, who sought to get away from excessive luxury and any images that could distract the monks from prayer and contemplation, expelled such decor from their monasteries.

3. Washbasin

IN Pure Thursday on Holy Week - in memory of how Christ washed the feet of his disciples before the Last Supper (John 13:5-11) - the monks, led by the abbot, there humbly washed and kissed the feet of the poor, who were brought to the monastery.

In the gallery that adjoined the church, every day before Compline, the brethren gathered to listen to the reading of some pious text - collatio. This name arose from the fact that St. Benedict recommended for this “Conversation” (“Collationes”) by John Cassian (about 360 - about 435), an ascetic who was one of the first to transfer the principles of monastic life from Egypt to the West. Then the word collatio began to be called a snack or a glass of wine, which on fast days was given to the monks at this evening hour (hence the French word collation - “snack”, “light dinner”).

4. Sacristy

A room in which liturgical vessels, liturgical vestments and books were kept under the castle (if the monastery did not have a special treasury, then relics), as well as the most important documents: historical chronicles and collections of charters, which listed purchases, donations and other acts from which depended on the material well-being of the monastery.

5. Library

There was a library next to the sacristy. In small communities, it looked more like a small closet with books, in huge abbeys it looked like a majestic vault in which the characters of Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose are looking for the forbidden volume of Aristotle.

What the monks read at different times and in different parts of Europe, we can imagine thanks to the inventories of medieval monastic libraries. These are lists of the Bible or individual biblical books, commentaries on them, liturgical manuscripts, writings of the Church Fathers and authoritative theologians (Ambrose of Milan, Augustine of Hippo, Jerome of Stridon, Gregory the Great, Isidore of Seville, etc.), lives of saints, collections of miracles, historical chronicles, treatises on canon law, geography, astronomy, medicine, botany, Latin grammars, the works of ancient Greek and Roman authors ... It is well known that many ancient texts have survived to this day only because they, despite their suspicious attitude towards pagan wisdom, were preserved by medieval monks.

In Carolingian times, the richest monasteries - such as St. Gallen and Lorsch in the German lands or Bobbio in Italy - possessed 400-600 volumes. The catalog of the library of the monastery of Saint-Riquier in northern France, compiled in 831, consisted of 243 volumes. A chronicle written in the 12th century at the monastery of Saint-Pierre-le-Vief in Sens, lists the manuscripts ordered to be rewritten or restored by the abbe Arnaud. In addition to biblical and liturgical books, it included commentaries and theological writings by Origen, Augustine of Hippo, Gregory the Great, the passion of the martyr Tiburtius, a description of the transfer of the relics of St. Benedict to the monastery of Fleury, the History of the Lombards by Paul the Deacon, etc.

In many monasteries, the library functioned as scriptoria, where the brothers copied and decorated new books. Until the 13th century, when workshops for lay scribes began to multiply in cities, monasteries remained the main producers of books, and monks their main readers.

6. Chapter Hall

The administrative and disciplinary center of the monastery. It was there that every morning (after the service of the first hour in summer; after the third hour and morning mass in winter) the monks gathered to read one of the chapters (capitulum) of the Benedictine Rule. Hence the name of the hall. In addition to the charter, they read out a fragment from the martyrology (a list of saints whose memory was celebrated on each day) and an obituary (a list of the deceased brothers, patrons of the monastery and members of his “family”, for whom the monks should offer prayers on this day).

In the same hall, the abbot instructed the brethren and sometimes consulted with selected monks. There, the novices who passed the probationary period again asked to be tonsured as monks. There the abbot received the mighty of this world and resolved conflicts between the monastery and church authorities or secular lords. The “accusatory chapter” also took place there - after reading the charter, the abbot said: “If someone has something to say, let him speak.” And then those monks who knew for someone or for themselves some kind of violation (for example, they were late for the service or left the found thing at least for one day), they had to confess to the rest of the brethren in it and suffer the punishment, which appointed by the pastor.

The frescoes that adorned the capitular halls of many Benedictine abbeys reflected their disciplinary vocation. For example, in the St. Emmeram Monastery in Regensburg, paintings were made on the theme of the “angelic life” of monks struggling with temptations, following the model of St. Benedict, their father and legislator. In the monastery of Saint-Georges-de-Bocherville in Normandy, on the arcades of the capitular hall, images of corporal punishment were carved, to which the guilty monks were sentenced.

Granet Francois-Marius (1775-1849) "Meeting of the monastery chapter". France, 1833

Canvas, oil. 97 x 134.5 cm.

State Hermitage.

7. Room for conversations

The Rule of Saint Benedict ordered the brethren most time to be silent. Silence was considered the mother of virtues, and a closed mouth was considered “a condition for the rest of the heart.” Collections of the customs of various monasteries sharply limited those places and moments of the day when the brothers could communicate with each other, and the lives described heavy punishments that fall on the heads of talkers. In some abbeys, a distinction was made between "great silence" (when it is forbidden to speak at all) and "little silence" (when one could speak in an undertone). In separate rooms - churches, dormitories, a refectory, etc. - idle conversations were completely prohibited. After Compline, there was to be absolute silence in the entire monastery.

In case of emergency, it was possible to talk in special rooms (auditorium). In Cistercian monasteries there could be two of them: one for the prior and monks (next to the chapter hall), the second, primarily for the cellar and convers (between their refectory and kitchen).

To facilitate communication, some abbeys developed special sign languages that made it possible to transmit the simplest messages without formally violating the charter. Such gestures did not mean sounds or syllables, but whole words: the names of various premises, everyday objects, elements of worship, liturgical books, etc. Lists of such signs were preserved in many monasteries. For example, in Cluny, there were 35 gestures for describing food, 22 for items of clothing, 20 for worship, etc. To “say” the word “bread”, one had to make a circle with two little fingers and two forefingers, since bread was usually baked round. In different abbeys, the gestures were completely different, and the gesticulating monks of Cluny and Hirsau would not have understood each other.

8. Bedroom, or dormitorium

Most often, this room was located on the second floor, above or near the chapter hall, and could be accessed not only from the cloister, but also through the passage from the church. The 22nd chapter of the Benedictine charter prescribed that each monk should sleep on a separate bed, preferably in the same room:

«<…>... but if their large number does not allow this to be arranged, let them sleep ten or twenty with the elders, on whom lies the care of them. Let the lamp in the bedroom burn until morning.

They should sleep in their clothes, girded with belts or ropes. When they sleep, let them not have their little knives with which they work, cut off branches and the like, so as not to injure themselves during sleep. The monks must always be ready and, as soon as the sign is given, get up without delay, hasten, preempting one another, to the work of God, decorously, but modestly. The youngest brethren should not have beds next to each other, but let them be mixed with the elders. Standing up for the cause of God, let them fraternally encourage each other, dispelling the excuses invented by the drowsy.

Benedict of Nursia instructed that the monk should sleep on a simple mat, covered with a blanket. However, his charter was intended for a monastery located in southern Italy. In northern lands—say, Germany or Scandinavia—observance of this directive required much greater (often almost impossible) selflessness and contempt for the flesh. In various monasteries and orders, depending on their severity, different measures of comfort were allowed. For example, Franciscans were required to sleep on bare ground or planks, and mats were only allowed for those who were physically weak.

9. Warm room, or calefactorium

Since almost all the premises of the monastery were not heated, a special warm room was arranged in the northern lands, where the fire was maintained. There the monks could warm up a little, melt the frozen ink or wax their shoes.

10. Refectory, or refectorium

In large monasteries, the refectories, which were supposed to accommodate the entire brethren, were very impressive. For example, in the Parisian abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the refectory was 40 meters long and 20 meters wide. Long tables with benches were placed in the shape of the letter "P", and all the brethren were seated behind them in order of seniority - just like in the choir of the church.

In the Benedictine monasteries, where, unlike the Cistercian ones, there were many cult and didactic images, frescoes depicting the Last Supper were often painted in the refectories. The monks had to identify themselves with the apostles gathered around Christ.

11. Kitchen

The Cistercian diet was mostly vegetarian, with the addition of fish. There were no special cooks - the brothers worked in the kitchen for a week, on Saturday evening the brigade on duty gave way to the next one.

For most of the year, the monks received only one meal a day, in the late afternoon. From mid-September until Lent (beginning around mid-February), they could eat for the first time after the ninth hour, and at great post— after supper. Only after Easter did the monks get the right to have another meal around noon.

Most often, the monastic dinner consisted of beans (beans, lentils, etc.), designed to satisfy hunger, after which they served the main course, which included fish or eggs and cheese. On Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, each usually received a whole portion, and on the days of fasting, Monday, Wednesday and Friday - one portion for two.

In addition, to support the strength of the monks, every day they were given a portion of bread and a glass of wine or beer.

12. Refectory for converse

In the Cistercian monasteries, lay brothers were separated from full-fledged monks: they had their own dormitory, their own refectory, their own entrance to the church, etc.

13. Entrance to the monastery

The Cistercians strove to build their abbeys as far as possible from cities and villages in order to overcome the secularization in which the “black monks”, primarily the Clunians, had been mired in the centuries since the time of St. Benedict. Nevertheless, the “white monks” also could not completely fence themselves off from the world. Lay people came to them, members of the monastic "family", connected with the brothers by ties of kinship or who decided to serve the monastery. The gatekeeper, who watched over the entrance to the monastery, periodically welcomed the poor, who were given bread and leftover food left uneaten by the brothers.

14. Hospital

In large monasteries, a hospital has always been set up - with a chapel, a refectory, and sometimes with its own kitchen. Unlike healthy counterparts, patients could count on increased nutrition and other benefits: for example, they were allowed to exchange a few words during meals and not attend all the long services.

All brothers were periodically sent to the hospital, where they underwent bloodletting (minutio), a procedure that was considered extremely useful and even necessary to maintain the correct balance of humors (blood, mucus, black bile and yellow bile) in the body. After this procedure, the weakened monks received temporary relief for several days in order to restore their strength: exemption from the all-night service, evening rations and a glass of wine, and sometimes delicacies like fried chicken or goose.

15. Other buildings

In addition to the church, the cloister and the main buildings where the life of monks, novices and converse passed, the monasteries had many other buildings: the personal apartments of the abbot; a hospice for poor wanderers and a hotel for important guests; various outbuildings: barns, cellars, mills and bakeries; stables, dovecotes, etc. Medieval monks were engaged in many crafts (made wine, brewed beer, dressed leather, processed metals, worked on glass, produced tiles and bricks) and actively mastered natural resources: they uprooted and felled forests, mined stone, coal , iron and peat, mastered salt mines, built water mills on rivers, etc. As we would say today, monasteries were one of the main centers of technical innovation.

Klodt, Mikhail Petrovich (1835-1914) "The Laundry in the Catholic Franciscan Monastery". 1865

Canvas, oil. 79 x 119cm.

Ulyanovsk Regional Art Museum.

Literature:

. Dyuby J. Time of cathedrals. Art and Society, 980-1420. M., 2002.

. Karsavin L.P. Monasticism in the Middle Ages. M., 1992.

. Leo of Marsicansky, Peter the Deacon. Chronicle of Montecassino in 4 books. Ed. prepared by I. V. Dyakonov. M., 2015.

. Moulin L. Everyday life medieval monks of Western Europe (X-XV centuries). M., 2002.

. Peter Damiani. Life of St. Romuald. Monuments of medieval Latin literature of the X-XI centuries. Rep. ed. M. L. Gasparov. M., 2011.

. Uskov N.F. Christianity and monasticism in Western Europe in the early Middle Ages. German lands II / III - mid-XI. SPb., 2001.

. Ekkehard IV. History of St. Gallen Monastery. Monuments of medieval Latin literature of the X-XII centuries. M., 1972.

. Monastic Rule of Benedict. Middle Ages in his monuments. Per. N. A. Geinike, D. N. Egorova, V. S. Protopopov and I. I. Schitz. Ed. D. N. Egorova. M., 1913.

. Cassidy-Welch M. Monastic Spaces and Their Meanings. Thirteenth-Century English Cistercian Monasteries. Turnout, 2001.

. D'Eberbach C. Le Grand Exorde de Cîteaux. Berlioz J. (ed.). Turnout, 1998.

. Davril A., Palazzo E. La vie des moines au temps des grandes abbayes, Xe-XIIIe siècles. Paris, 2010.

. Dohrn-van Rossum G. L'histoire de l'heure. L'horlogerie et l'organization moderne du temps. Paris, 1997.

. Dubois J. Les moines dans la société du MoyenÂge (950-1350). Revue d'histoire de l "Église de France. Vol. 164. 1974.

. Greene P. J. Medieval Monasteries. London; New York, 2005.

. Kinder T. N. Cistercian Europe: Architecture of Contemplation. Cambridge, 2002.

. Miccoli G. Les moines. L'homme mediéval. Le Goff J. (dir.). Paris, 1989.

. Schmitt J.-C. Les rythmes au MoyenÂge. Paris, 2016.

. Vauchez A. La Spiritualité du Moyen Âge occidental, VIIIe-XIIIe siècle. Paris, 1994.

. cluny. Roux-Périno J. (ed.). Vic-en-Bigorre, 2008.

. Elisabeth of Schonau. The Complete Works. Clark A. L. (ed.). New York, 2000.

. Raoul Glaber: les cinq livres de ses histoires (900-1044). Prou M. (ed.). Paris, 1886.

Cuvier Armand (active c. 1846) "The Monastery of the Dominicans at Voltri". France, Paris, first half of the 19th century.

Chinese paper, lithograph. 30 x 43 cm.

State Hermitage.

Hanisch Alois (b. 1866) "Melk Monastery". Austria, late 19th - early 20th century.

Paper, lithography. 564 x 458 mm (sheet)

State Hermitage.

J. Howe "The Procession of the Monks". UK, 19th century

Paper, steel engraving. 25.8 x 16 cm.

State Hermitage.

This is Louis (1858-1919) "Thistle flower with a view of the monastery in the background." Album "Golden Book of Lorraine". France, 1893 (?)

Paper, ink pen, watercolor. 37 x 25 cm.

State Hermitage.

Stefano della Bella (1610-1664) View of the Monastery of Villambrosa. Sheets from the suite of illustrations for the biography of St. John Gualbert "Views of the Monastery of Villambroso". Italy, 17th century

Paper, etching. 17.4 x 13.2 cm.

State Hermitage.

Bronnikov Fedor Andreevich (1827-1902) "Capuchin". 1881

Wood, oil. 40.5 x 28 cm.

Kherson Regional Art Museum named after A.A. Shovkunenko.

Eduard von Grützner (1846-1925) Monk with a Newspaper. Germany, third quarter of the 19th century.

Canvas, oil. 36 x 27 cm.

State Hermitage.

Callot Jacques (1592-1635) Pogrom of the monastery. Sheets from the suite "The Great Disasters of War (Les grandes miseres de la guerre)". France, 17th century

Paper, etching. 9 x 19.4 cm

State Hermitage.

Unknown Flemish artist, con. 17th century "The Hermit Monks". Flanders, 17th century

Wood, oil. 56 x 65.5 cm.

State Hermitage.

The monasteries arose out of the desire of hermits for a spiritual life outside of society, but in the community. Prince Siddhartha Gautama renounced wealth in search of enlightenment, becoming the founder of a Buddhist community of monks.

Christian monasticism arose in the desert of Egypt, where hermits sought a solitary life. Some were so revered and famous that they turned their followers into disciples who formed communities in the 4th century. So Anthony gathered the hermits who lived nearby in the desert, who gathered on Sundays for worship and a common meal. One of the oldest monasteries in the world was founded shortly after the death of St. Anthony, named after him as the founder of Christian monasticism.

Monasticism gradually spread throughout the Roman Empire. Saint Benedict also fled from the world, but the disciples paved the way to his door. In 530, he enclosed the community with a wall and wrote rules for the monks, where he emphasized obedience, moderation and an even alternation of work and prayer, founding Monte Cassino, the first monastery in Italy. So the monastic movement began to spread in Europe. Since the VI century began to build monasteries in England and Ireland.

In Kievan Rus, monasticism began after the adoption of Christianity. Kiev-Pechersky is one of the first monasteries in Ukraine, founded in 1051 by the monk Anthony, originally from Lyubech.

Communal buildings were required for communal life. The church was a priority - prayers were the main occupation of the monks. The dormitory, refectory and other buildings were located around the monastery, the temples were preferably on the south side in the sun. There were also a kitchen, a bakery, workshops and workshops. Life was quiet, without noise and fuss. Hospitality was part of the monastery rule, the guest house was usually located in the outer courtyard. In popular pilgrimage centers guest houses were overloaded, and the monasteries built hotels in the city, outside the monastic cloister. The estates and guest houses belonging to the monasteries became the main source of their income.

Throughout the centuries, monks and nuns have done many good deeds. They collected books and copied them, opened schools and hospitals. The monks were the most educated members of society, and often the only educated. Medieval monasteries were also places of distribution of alms to the poor.

At the beginning of the XIV century, monasteries in England were the most numerous. In 1530, Henry VIII severed relations with Rome and dissolved most of the monasteries. Some of them near large villages were preserved as cathedrals or parish churches, others were sold to wealthy families, the rest were demolished. The monasteries did not return to England until centuries later.

The prestige of religious communities suffered from anti-church sentiment at the end of the 18th century (the culmination of the struggle against the Jesuits), many of them were destroyed. Especially in France during the French Revolution (for example, one of the most ancient). The monasteries were never again able to regain the power they once held.

Nevertheless, in the 19th century, religious sentiments returned in society, and a revival of the great Christian monuments of the Middle Ages began, when monasticism was at its peak. By the end of the 20th century, in most Western countries, monks again stepped up their activities in the educational and charitable fields, devoting themselves to the first goal of monasticism - contemplation.

We have repeatedly referred to the plan preserved in the Saint-Gallen monastery, which conveys in great detail the internal structure of the monastery of the 9th century. On the drawing - the most diverse services of the monastery; The value of this document is increased by the fact that it, apparently, is not a plan of this or that particular monastery, but a model plan according to which all monasteries were to be built.

It is interesting to note, as a feature of naivete, characteristic of that era, that all explanations for the plan, which are of a more general nature, are set out in verse. In prose, only a description is given that is directly related to the Saint-Gallen monastery, for example, the name of the saint to whom the main altar will be dedicated, the dimensions of the length and width of the church, in a word, local details. Obviously, these rhymed inscriptions were not composed for the sake of an isolated case, but represent the points of a general statute, an instruction addressed to all abbeys equally.

| Rice. 340 |

We play on the left side rice. 340 this standard plan in general terms. With a free arrangement of services, it resembles the plan of a Roman villa. As in an ancient villa, the laws of symmetry are not observed at all here: the buildings are located on vast areas, according to the conditions of the terrain and convenient use.

Note: The plan of Saint Gallen Abbey dates back to 820. The fact that this plan is, so to speak, an exemplary plan, which should have guided the construction of other monasteries, speaks for the predominance in the early Middle Ages of the desire for typological and stylistic uniformity of forms in both civil and in religious buildings, both in separate buildings (basilica, donjon), and in architectural complexes (monastery, castle, city); see below. For the plan of St. Gallen Abbey, see Otte, Geschichte der Roman. Baukunst in Deutschland, 1874, p. 92; Last eyrie, L "architecture religieuse en France a l" epoque romane, Paris 1912, p. 141.

On the plan of the abbey, as well as on the plan of the Roman villa, two main parts are distinguished: villa rustika and villa urbana (rural villa and urban villa). The latter, in fact, became a monastery; as in an ancient house, here the halls surround a courtyard with porticos, and the atrium has been transformed into a covered gallery (cloister). The plan of the Saint-Gallen monastery can be briefly described as follows: in the center - the church; on the south side - rooms for monks and a room for pilgrims; on the north side - the premises of the abbot, schools, hotels; behind is a hospital, far removed from the monastery; in the vicinity - a farm and housing for laity workers.

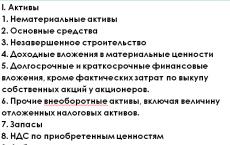

The following list elaborates on this general plan:

K - bedrooms located along the covered gallery and communicating with the choir;

R - refectory, with kitchen (S) and pantry (C);

A - the abbot's quarters;

B - workshop of copyists and library;

H - room for guests;

R is a place for pilgrims, beggars and, no doubt, also for asylum-seekers;

M - hospital with a special chapel; to the left of the chapel - a hospital for clerics, to the right - for strangers;

F - farm and workshops belonging to the abbey.

As a detail, the plan points to a heater or underfloor heating located under the bedroom, which at the same time serves to heat the bathhouse located in courtyard L, as well as to the pulpit for reading prayers in the refectory.

For comparison with the plan of the St. Gallen monastery, we place the plan of the abbey of Clairvaux of the XII century. (Fig. 340, right). The similarity between these plans is so great that it would be superfluous to give each of them a special explanation; therefore we have marked on both planes the same services by the same letters.

Look at the description of the St. Gallen monastery - it corresponds to the abbey in Clairvaux; the plan of Clairvaux seems to be the actual implementation of the standard plan, as applied to the requirements of the locality and to certain special conditions of the statute. Here are the most significant differences: in the monastery of St. Gallen there was only one covered gallery - in Clairvaux there are two, the second being for scientific studies; instead of a bedroom above the heater (hypocauste), there is a bedroom without a fireplace, located on the second floor, and below it there is a chapter hall, a reception room, a small room reserved for conversations with visitors, occasionally allowed to the monks, and a closet where the monks warmed themselves after the night service.

In general, in all the abbeys and throughout the Middle Ages, the premises were distributed in the same spirit as they were dictated in the 9th century. graphic indications of the plan of the Saint-Gallen monastery. Only the Order of St. Bruno makes changes to this plan, expressed in the fact that each monk is assigned a separate small cell in the corner of the courtyard (the Carthusian monastery, now destroyed, in Clermont; partly preserved Carthusian monastery in Nuremberg).

In addition to the agricultural buildings adjoining the monastery, the great abbeys owned individual farms, the architecture of which, while retaining the character of simplicity dictated by their purpose, is sometimes so artistically perfect that these buildings can be considered first-class works of art. Such is the farm at Mesle near Tours, the remaining parts of which are depicted on rice. 341.

Some of the monastery mills are also real architectural monuments.

Let us finally mention the monasteries-fortresses, such as Mont Saint-Michel, whose multi-storey buildings rise on the slopes of a cliff rising in the middle of the sea. Such fortified monasteries are an exception; usually they are content with a battlement with turrets at the corners, relying on respect for the sacred place.

Chapter "Monastic buildings" of the section "Monastic and civil architecture of the Middle Ages" from the book of Auguste Choisy "History of Architecture" (Auguste Choisy, Histoire De L "Architecture, Paris, 1899). Based on the publication of the All-Union Academy of Architecture, Moscow, 1935.

We all heard about monasteries in France, Spain, Italy, Greece... but almost nothing is known about German monasteries, and all because due to the Reformation of the Church in the 16th century, most of them were abolished and have not survived to this day. . However, in the south of Germany near Tübingen, one very interesting monastery has been preserved.

Bebenhausen was founded in 1183 by the count palatine of Tübingen and the monks of the Cistercian Order settled there, although the monks of another Order, the Premonsians, built the monastery, but for some reason they left the monastery a couple of years after its construction. The monastery was quite rich and owned good allotments, on which the monks were engaged in agriculture, including the cultivation of vineyards. The independence of the monastery was ensured by the charter of Emperor Henry VI and the bull of Pope Innocent III. In addition, the monastery owned a large area of forest where it was possible to hunt. In 1534, the monastery was abolished due to the fact that Protestantism came to these lands and Catholic monasteries were no longer needed here, but the monks continued to live here until 1648. Since then, the monastery has been used as a Protestant school, at one time was the residence of the Württemberg kings, who hunted in the same forest, and was also used as a place where the regional parliament met. Now it is just a museum, but the monastery is unique in that it has been preserved much better than others. The architecture of the monastery is an excellent example of the German Gothic of the late 15th century. The original Romanesque buildings of the 12th and 13th centuries were simply rebuilt.

Plan of the monastery

There is no more than a kilometer from the northern outskirts of Tübingen, so you can do without a car. In addition, there are buses between and Tübingen with a stop at the monastery - 826 (828) and 754, plying between Sinterfingen and Tübingen.

For those who drive, just turn off the L1208 road and almost immediately you will see free parking right at the very walls of the monastery.

Just right in front of the red bus goes

The monastery itself is more like a medieval, fortified village. There are powerful walls and towers here, but there are also cozy private houses, as well as vegetable gardens. Go beyond the walls is not difficult - it's free. You can see most of the monastery in this way.

First you go up the stairs and fall behind the first walls

Then we rise even higher

One of the two fortification towers

parade ground

Green tower. Apparently named after the color of the tiles.

Between the walls

Village behind the walls

This former House abbots, now the directorate of the museum is located here

House of Abbots

This, as I understand it, is the castle of the kings of Württemberg. It consists of several halls and a kitchen and is connected by a corridor with the main building of the monastery.

Corridor connecting the castle and monastery

Hall under the main building of the castle

Beyond the walls

The main building of the monastery on the right

In the depths of the courtyard, against the back walls, there is a monastery church, but there is no entrance to it.

In this part of the monastery, near the walls, there is a monastery cemetery.

Here on the corner of the walls is the second fortification tower - the Recording Tower (Schreibturm). Below it is another entrance to the monastery, obviously the main one.

Houses outside the walls of the monastery. There is another public car park here.

South wall of the monastery

Western wall of the monastery

record tower

Abbots' house

medicinal garden

And finally, having gone around the entire territory of the monastery, we approached the main building

Here you can buy a ticket and see the main building of the monastery and its church. At the checkout, do not forget to ask for a description of the monastery in Russian, then you will be given a pack of files that will tell you about all the premises of the monastery

At first glance, this is just a souvenir shop with cash desks, in fact there was a monastery kitchen, as evidenced by the preserved oven. According to the monastery charter, the monks ate here 2 times a day, and in winter, due to the shortened daylight hours - only 1 time. The diet consisted of 410 grams of bread, vegetables, fruits and eggs. Sick brothers were allowed to eat meat. On holidays they gave white bread, fish, wine.

Inside the monastery, traditional galleries around the garden await us.

The first hall in this part of the monastery will be the refectory, it was located right next to the kitchen, but until the end of the 15th century, laymen, not monks, ate here. In 1513, a refectory was built on this site - that is, a warm heated room for winter time (the room was heated by stoves located in basement). This is the winter dining hall.

There are many interesting patterns on the carved columns that support the ceiling, including pretzel and crayfish.

The fresco depicts the visit of Abbot Humbert von Sieto in 1471

The walls and ceilings of the hall are decorated with coats of arms of the founders of the monastery, monks, abbots and German princes.

From 1946 to 1952, the local Landtag met here

From the winter refectory we find ourselves in the refectory of novices, which until 1513 was a pantry. This room, like the next one, was heated. The painting on the ceiling is original and dates back to 1530. A door in the far right corner led to the novices' bedrooms.

As for the number of novices, there is information that at the end of the 13th century there were 130 people at the monastery at once. The novices ate the same as the monks.

Now there is a small museum of the treasures of the monastery.

Pay attention to the arrow of St. Sebastian, this is how they tried to kill him. The relic is very important, since Saint Sebastian was believed to protect against the plague, and because of it, many people died in the monastery at one time.

From the part of the monastery intended for novices, we find ourselves in the northern wing of the gallery. Here the monks read, and also some rituals took place here, for example, washing the feet. In addition, dead brothers were often buried in this wing. On the other side of the gallery is the entrance to the monastery church, there are carved marks on the wall about the size of the burial places of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, which were brought from the holy land by Count Eberhard in 1492

West gallery, novices wing

Here on the walls after the Reformation, many left information about themselves

From the northern wing of the gallery we get to the monastery church in honor of the Virgin Mary. It was built in 1228. This is a three-nave Romanesque basilica, very austere, as befits the architecture of the Cistercians. Indeed, before the Reformation

the church was decorated much richer, in particular, it contained as many as 20 altars.

According to the monastic daily routine, services were held here 7 times during the day and 1 time at night.

The most noteworthy detail here is the office (pulpit) of 1565, decorated with stucco

Immediately at the entrance to the church there is a staircase that leads to the cells of the monks - the dormitorium. This is the only place in the monastery where the second floor is available to visitors. Until 1516 there was a common bedroom, then separate rooms (cells) appeared. The walls and ceiling are decorated with floral motifs. In addition, at the entrance, inscriptions from the monastery charter have been preserved. The tiles here are also ancient, dating back to the 13th century. In the middle of the 20th century, when the Landtag was located in the monastery building, parliamentarians slept here

One of the rooms is available for viewing.

Washbasins

At the stairs to the floor there are a number of rooms, for example, there was a library and archive of the monastery.

The first room on the ground floor of this part of the building is the chapter house, the place where the monks used to gather. This happened every day at 6 am. There were benches along the walls, and the abbot sat opposite the entrance. Also, the most worthy were buried here, as evidenced by a large number of tombstones. This is the oldest part of the monastery, it dates back to 1220. The vaults were painted in 1528.

To the left at the far end of the chapter house is a small room, here in 1526 Archduke Ferdinand of Austria lived, preparing for confession

The next room in the east wing is the parlatorium. The fact is that according to the charter, the Cistercian monks were forbidden to speak, the only room where this could be done was the parlatorium. Moreover, it was possible to come here only for a short conversation on the case. Initially, a staircase led up to the bedrooms, but in the 19th century it was destroyed.

Under the floor of the hall was a heating installation, which was older than the monastery itself.

Some of the exhibits are now on display.

On the color scheme of the monastery, you can see which eras certain parts of the building belong to.

In the southern wing of the building there is one of the largest and most beautiful premises of the monastery - the Summer Refectory. It was built in 1335 in the Gothic style to replace a similar Romanesque building.

The walls here are decorated with coats of arms

And the original ceiling painting tells about flora and depicts fantastic animals

And only here, in the southern wing of the galleries, I discovered that their vaults were decorated no less exquisitely. Each intersection is crowned with 130 relief decorations and none of them is repeated. Initially, a calofactory (heated room) was located in this part, but after it was built to the west, the one located here was destroyed.

And the last room of the monastery, accessible to visitors, is the source, a kind of gazebo, located opposite the entrance to the refectory. In the center of this room was a fountain with drinking water, in addition, the brothers washed their hands here before eating. Unfortunately, the room itself and the fountain were destroyed and were only restored in 1879.

Above the entrance to the room with the source, two interesting images have been preserved.

The man in the fur hat appears to be a builder himself

And this is the legendary jester and joker, the hero of fairy tales - Til Ulenspiegel

And after exploring all the halls of the monastery, we finally go out into the garden with a fountain

The 19th century fountain

As you can see, all the galleries had a second floor, unfortunately, only the dormitorium in the east wing is available to tourists.

In the warm season, the monastery is open every day from 9 to 18.00, and only on Mondays there is lunch from 12 to 13 hours. In winter, the monastery is closed on Mondays, and on other days it is open from 10 am to 12 pm and from 1 pm to 5 pm. The ticket costs 5 euros. True, shooting on the territory is paid. In addition, separately, but only with a guide, on the territory of the monastery you can see the palace of the Württemberg kings of the 19th century, as well as the castle kitchen.

If you are in these parts, then do not forget to see Tübingen itself - very interesting city. You can also stay there for the night, I recommend the hotel for this